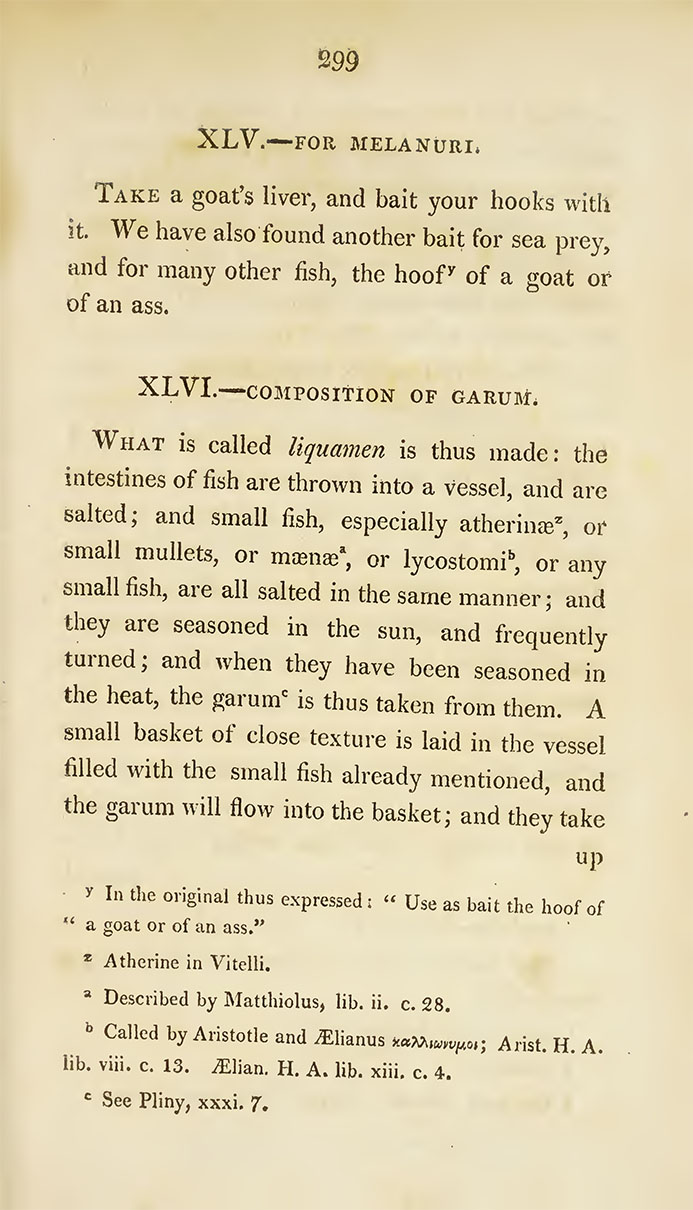

O QUE ACONTECE NO GARUM

A designação Garum é utilizada de forma genérica para definir molhos de peixe obtidos a partir da fermentação em salmoura, onde atuam microrganismos e enzimas presentes no pescado.

Garum é frequentemente imaginado como um molho produzido por meio de putrefação do peixe, e portanto inaceitável para a maioria dos consumidores modernos.

Para compreender a importância e o sucesso das conservas de peixe nas dietas antigas e modernas e para dissipar preconceitos sobre o seu gosto, devemos mencionar os complexos processos bioquímicos e enzimáticos que os produzem.

Segundo Harold McGee, autor americano que escreve sobre a química e a história da ciência alimentar e culinária, quando falamos de Garum podemos classificar o processo como uma “decomposição benigna”.

O que torna o Garum delicioso é precisamente o processo de decomposição química, que desenvolve todo o seu sabor.

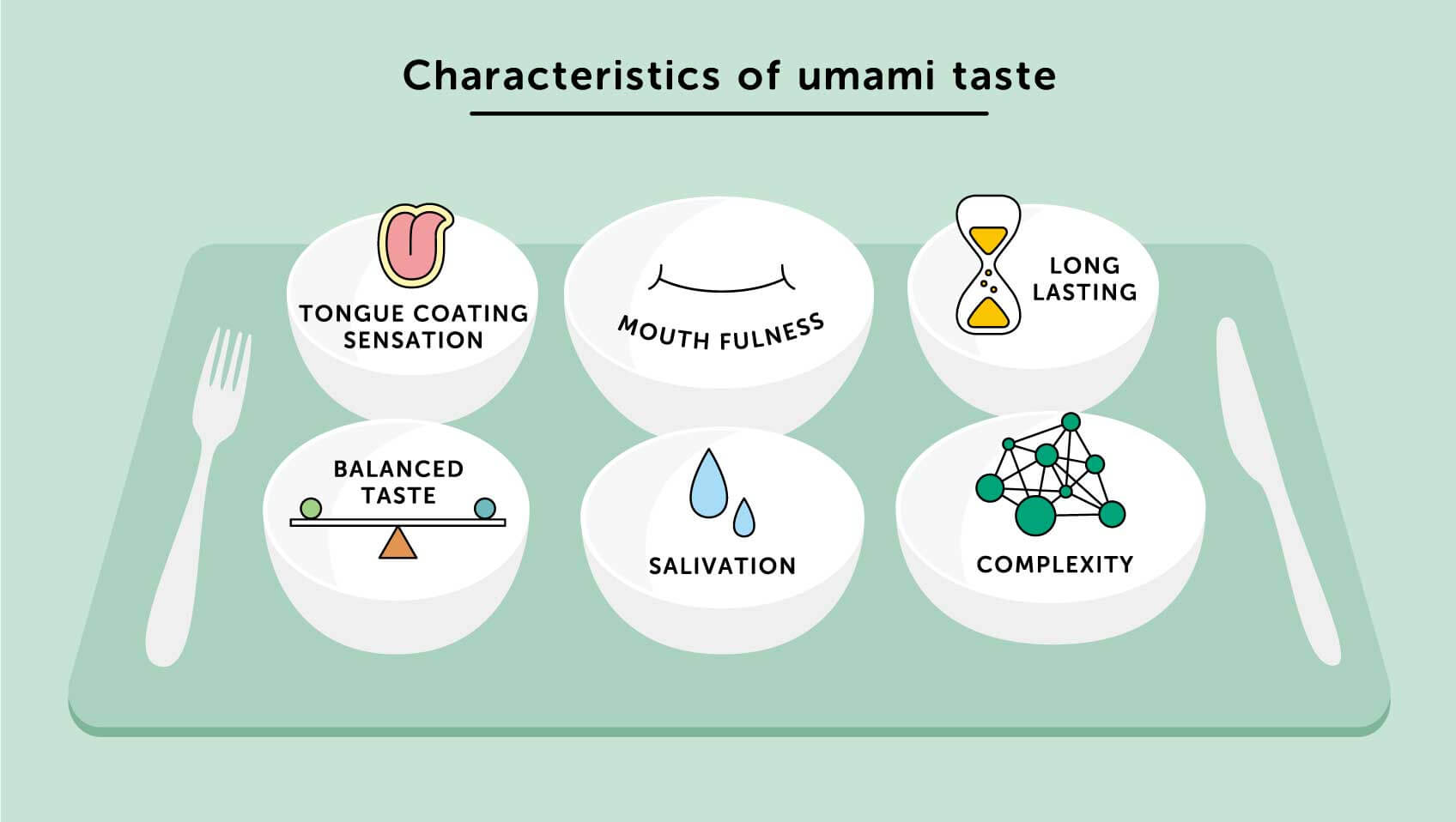

As aspectos que caracterizam o gosto umami são o facto de se espalhar globalmente pela língua, a sensação é mais duradoura que a dos outros gostos básicos e proporciona uma sensação de “dar água na boca”.

As moléculas muito grandes como proteínas, hidratos de carbono, gorduras e óleos, não possuem nenhuma qualidade que possamos registrar com os nossos sentidos químicos.

Através do paladar e olfato apenas conseguimos registrar a presença de pequenas moléculas. São estas pequenas moléculas que podemos “agarrar”, enviando uma mensagem de reconhecimento ao nosso cérebro.

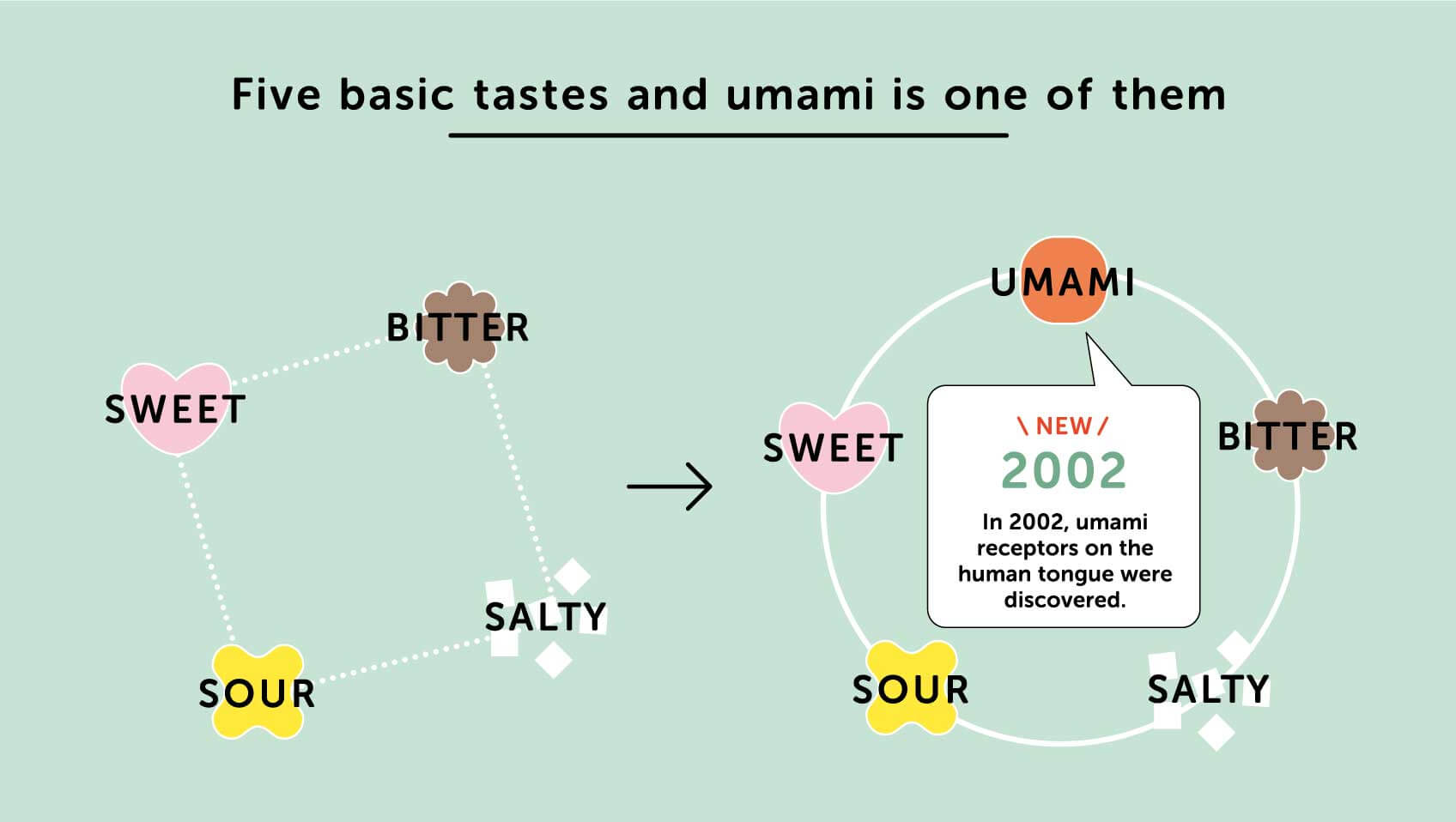

No paladar, temos genericamente cinco sentidos: salgado, azedo, doce, amargo e, recentemente, o umami, que nos dá a sensação de saboroso.

Existem milhares de aromas em nosso mundo natural que podemos captar e identificar, mas essas moléculas precisam ser suficientemente pequenas para que possam voar e alcançar o nosso nariz.

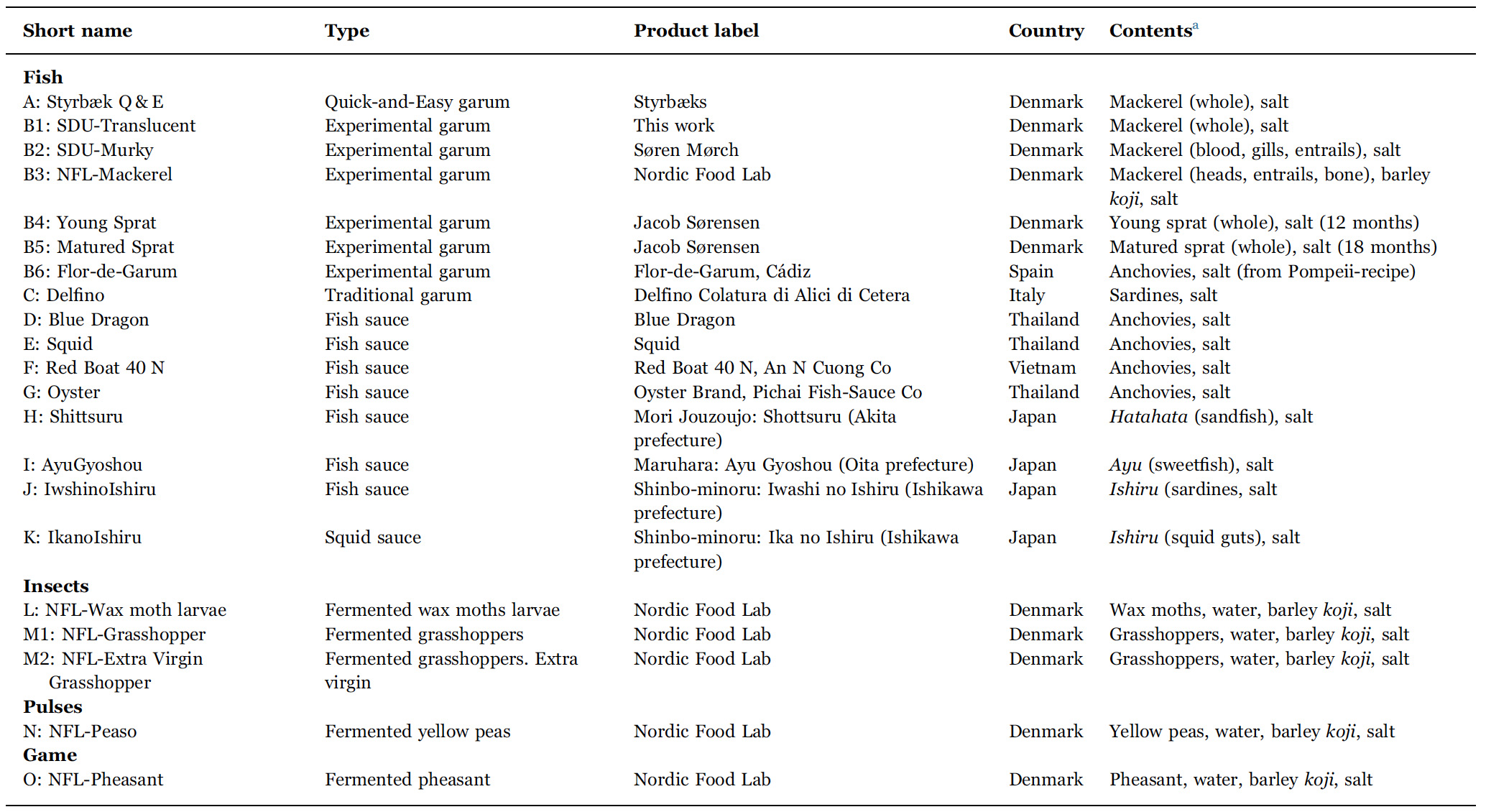

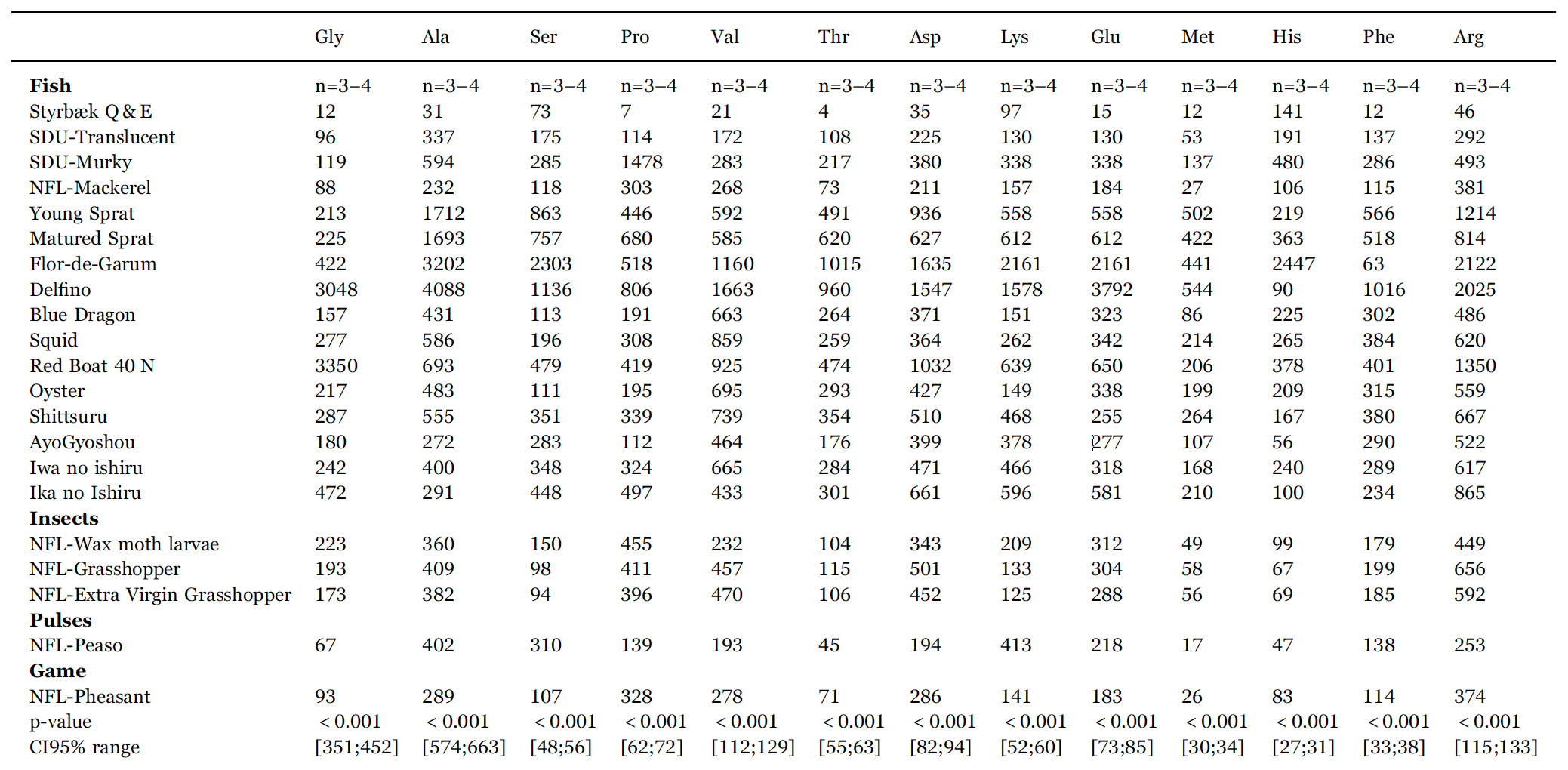

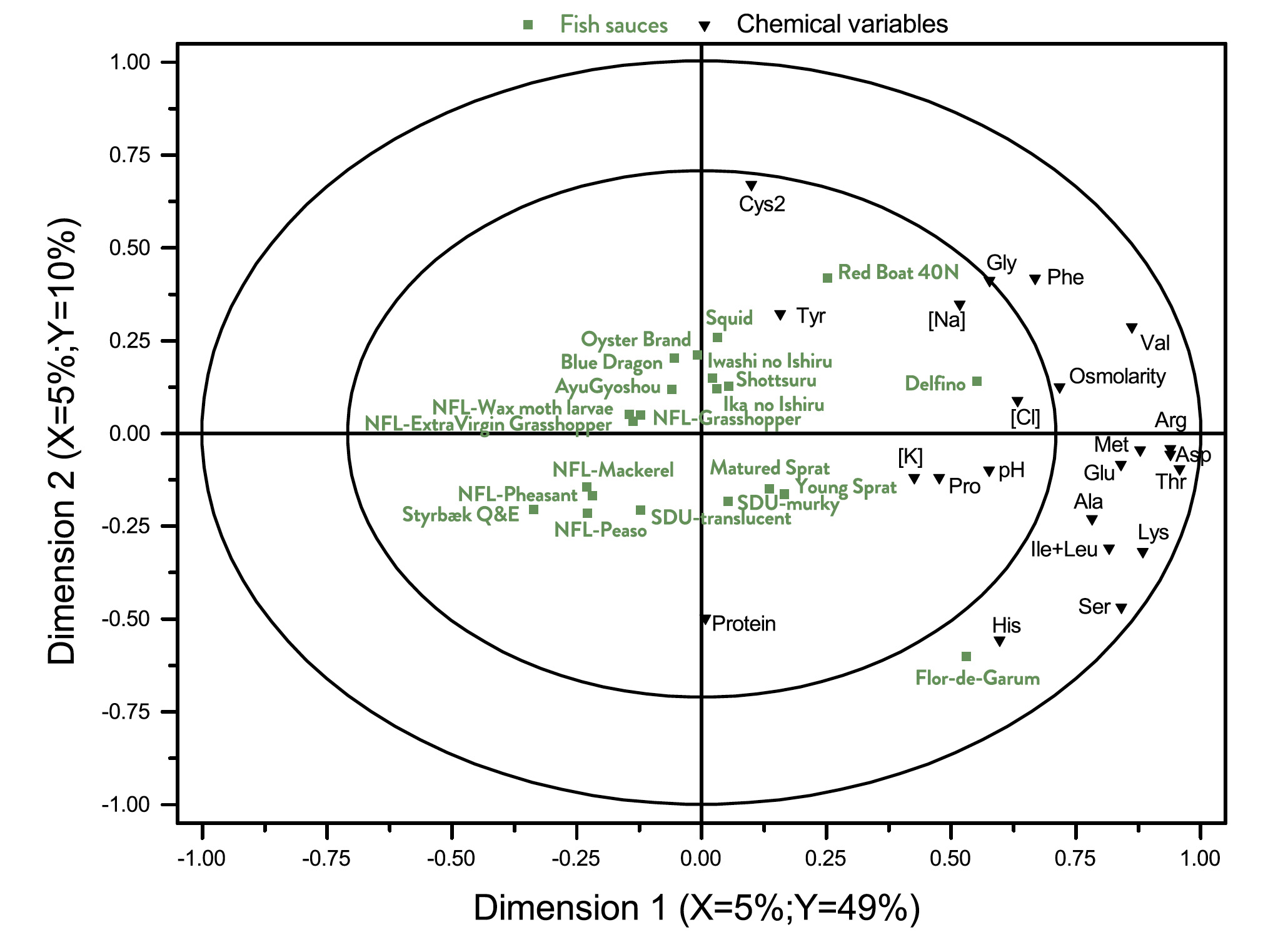

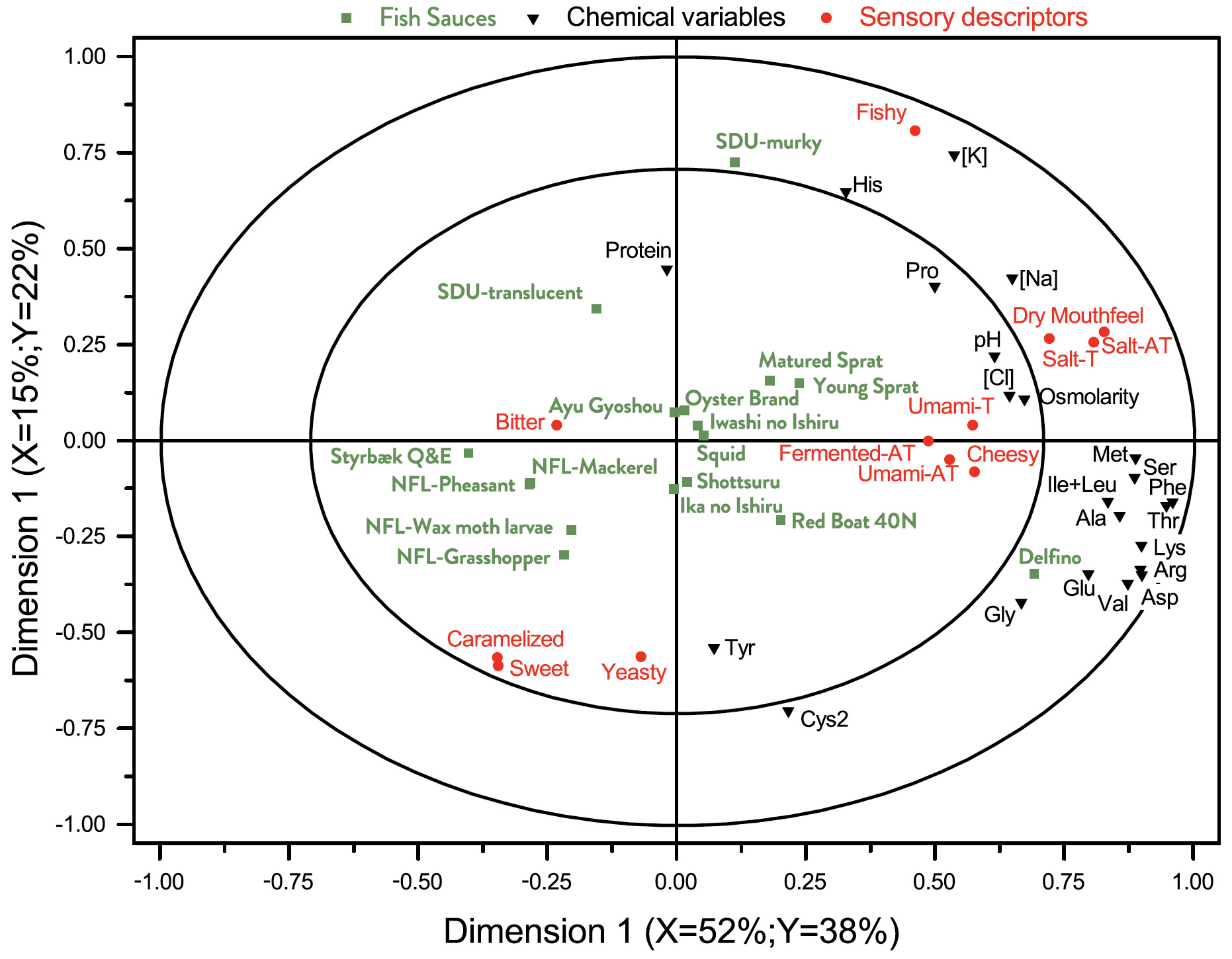

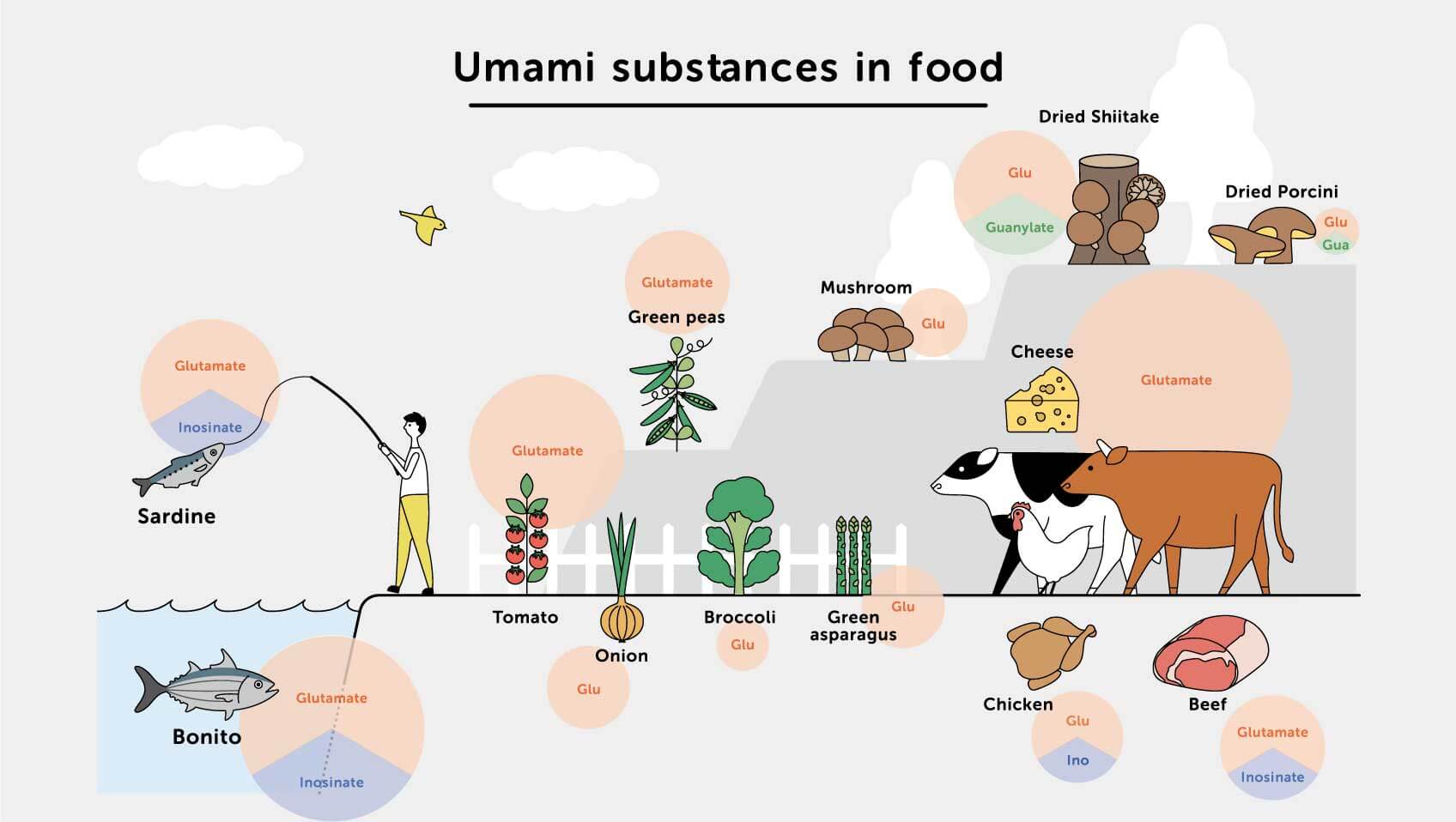

Assim a chave para fazer um Garum é quebrar as grandes moléculas do peixe, principalmente constituído por proteínas e óleo. As proteínas consistem em grandes moléculas construídas por blocos de moléculas mais pequenas que são os aminoácidos. Alguns aminoácidos são suficientemente pequenos para serem detetados pelos sensores na nossa língua. Uns são doces, outros são amargos, salgados ou azedos e alguns dão a sensação de saboroso, ou umami, como é o caso do ácido glutâmico cujos sais são conhecidos como glutamato.

O glutamato é um importante neurotransmissor que funciona como um intensificador de sabor. Pensa-se que o glutamato esteja envolvido nas funções cognitivas no cérebro, como a aprendizagem e a memória.

O que é diferenciador no umami, quando comparado com os restantes sabores, é que enquanto no salgado, azedo, doce e amargo, existem uma grande quantidade de moléculas, no umami existem poucas, mas todas relacionadas ao metabolismo das proteínas, especialmente o glutamato, que são as mais eficazes.

No processo de produção de Garum, as proteínas do peixe são partidas em aminoácidos, principalmente ácido glutâmico e glutamato, que nos dá a sensação de umami, tão rara no resto das nossas captações de sabor.

O facto do garum ter sido tão apreciado nos tempos antigos deveu-se provavelmente à alta concentração de glutamato monossódico, o sal sódico do ácido glutâmico, um dos aminoácidos não essenciais mais abundantes que ocorrem na natureza, que é encontrado naturalmente em alimentos como tomate, cogumelos ou queijo parmesão.

Imagens retiradas de www.ajinomoto.com

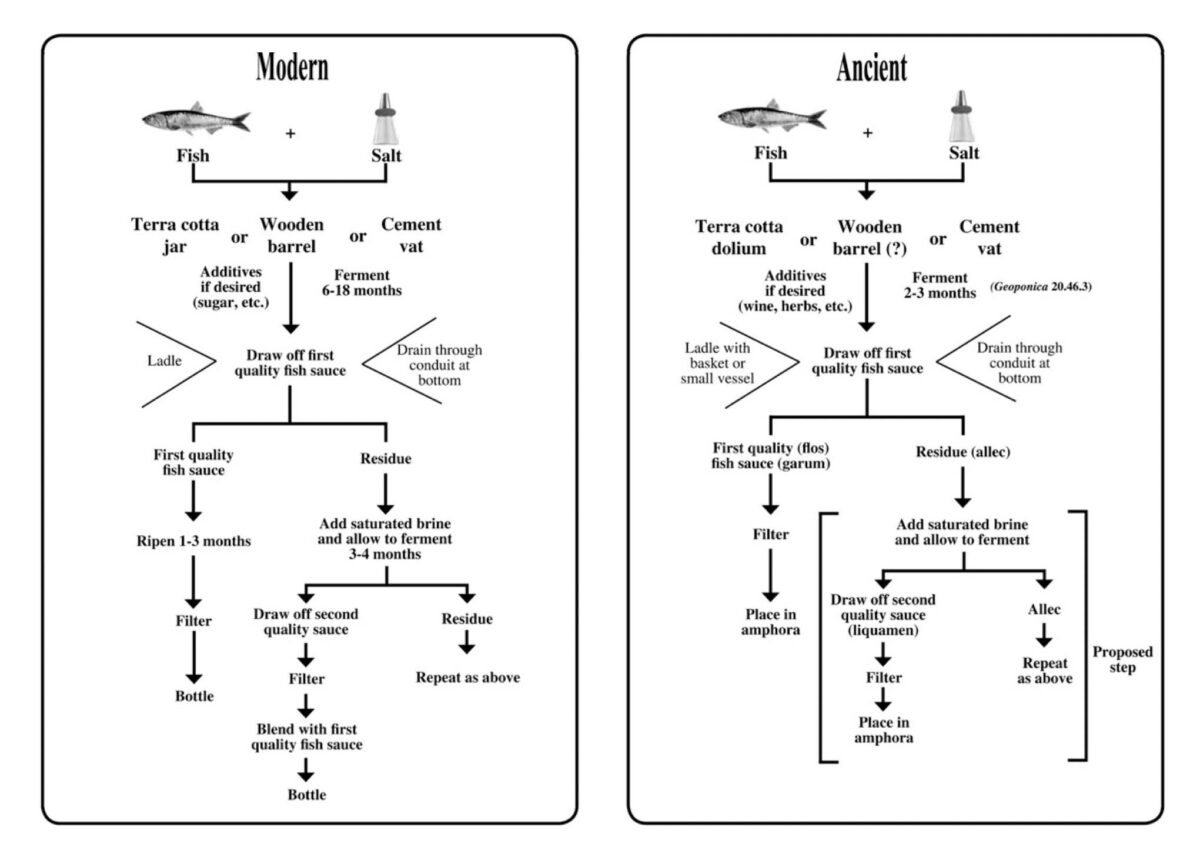

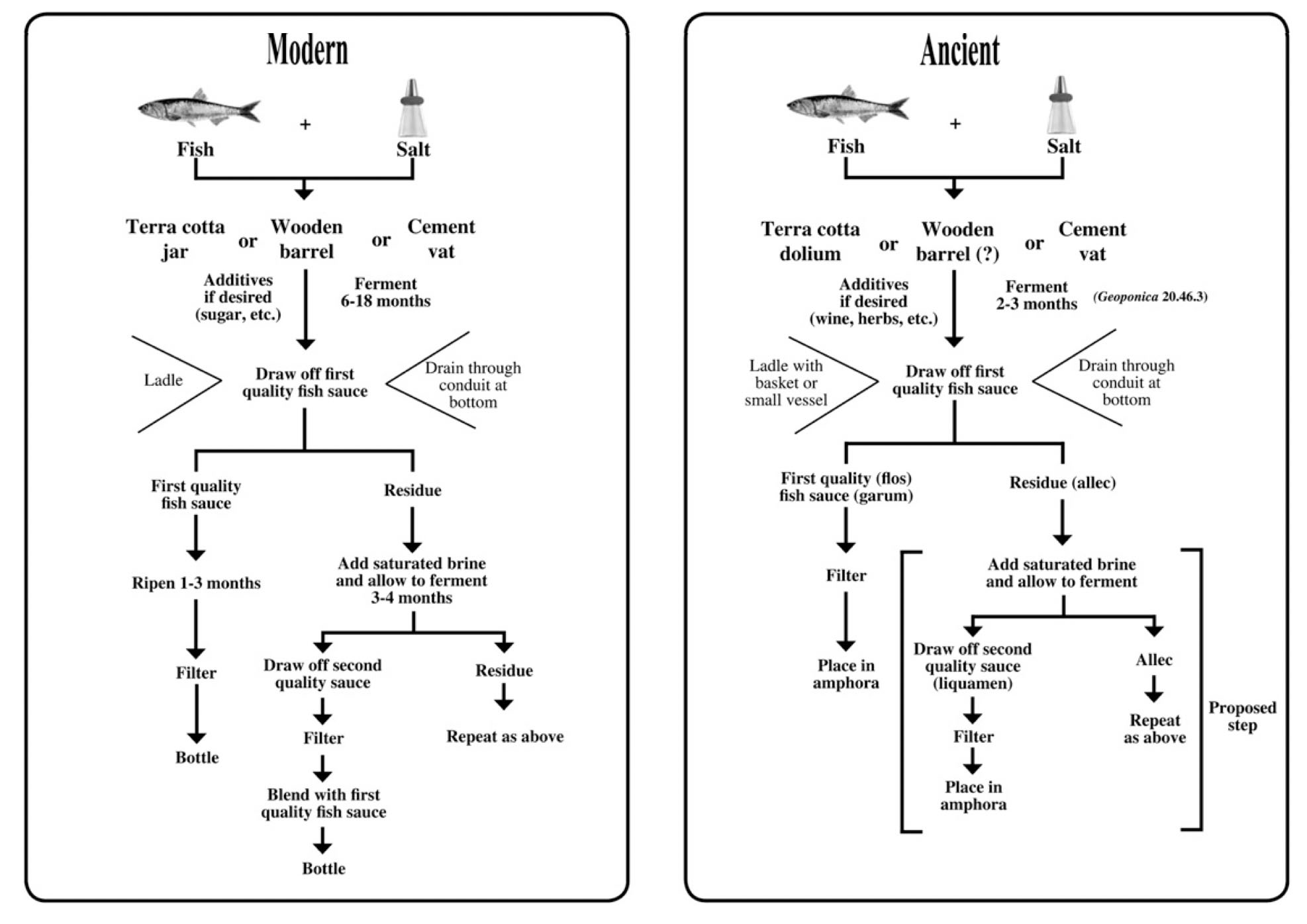

O processo

O processo de quebra das proteínas ocorre graças à ação de enzimas. As enzimas são também proteínas, mas especializadas no trabalho de quebra de outras moléculas, incluindo as proteínas.

Quando um peixe é capturado e morre, e os seus sistemas param de funcionar adequadamente, a ação das enzimas é revertida gradualmente apenas para a decomposição.

Após a morte, o peixe, como todos os outros animais, passa por uma série processos de decadência cujo primeiro passo é a autólise: a degeneração das células e órgãos através de substâncias químicas, processos desencadeados por enzimas intra-celulares. As enzimas intracelulares, que existem dentro das células que compõem o tecido, quebram lentamente as proteínas do tecido muscular em aminoácidos, incluindo o glutamato, e é dessa forma que o sabor se desenvolve.

A velocidade do processo autolítico aumenta com o aumento da temperatura ambiente, mas podem ser interrompidos se as texturas forem rapidamente congeladas ou desidratadas.

Em consequência da degeneração autolítica dos órgãos do trato gastrointestinal, a flora bacteriana do trato intestinal espalha-se pelo resto do cadáver, iniciando um processo chamado putrefação, a segunda fase da decomposição.

A atividade bacteriana produz inicialmente gases como dióxido de enxofre, dióxido de carbono, amónia, metano etc. e continua com a destruição das proteínas musculares e a produção de aminas tóxicas, como a cadaverina e putrescina.

A verdadeira salga, aquela usada para produzir peixe salgado e carne, produz uma desidratação dos tecidos que bloqueia a autólise, mas precisa de uma grande quantidade de cloreto de sódio (NaCl), processo que podemos comparar à produção de presunto. Neste caso, trata-se de carne da perna de porco, que é salgada para não se estragar, ou seja, não entrar em putrefação, e assim, ao longo dos meses, as enzimas vão decompondo as proteínas dos músculos.

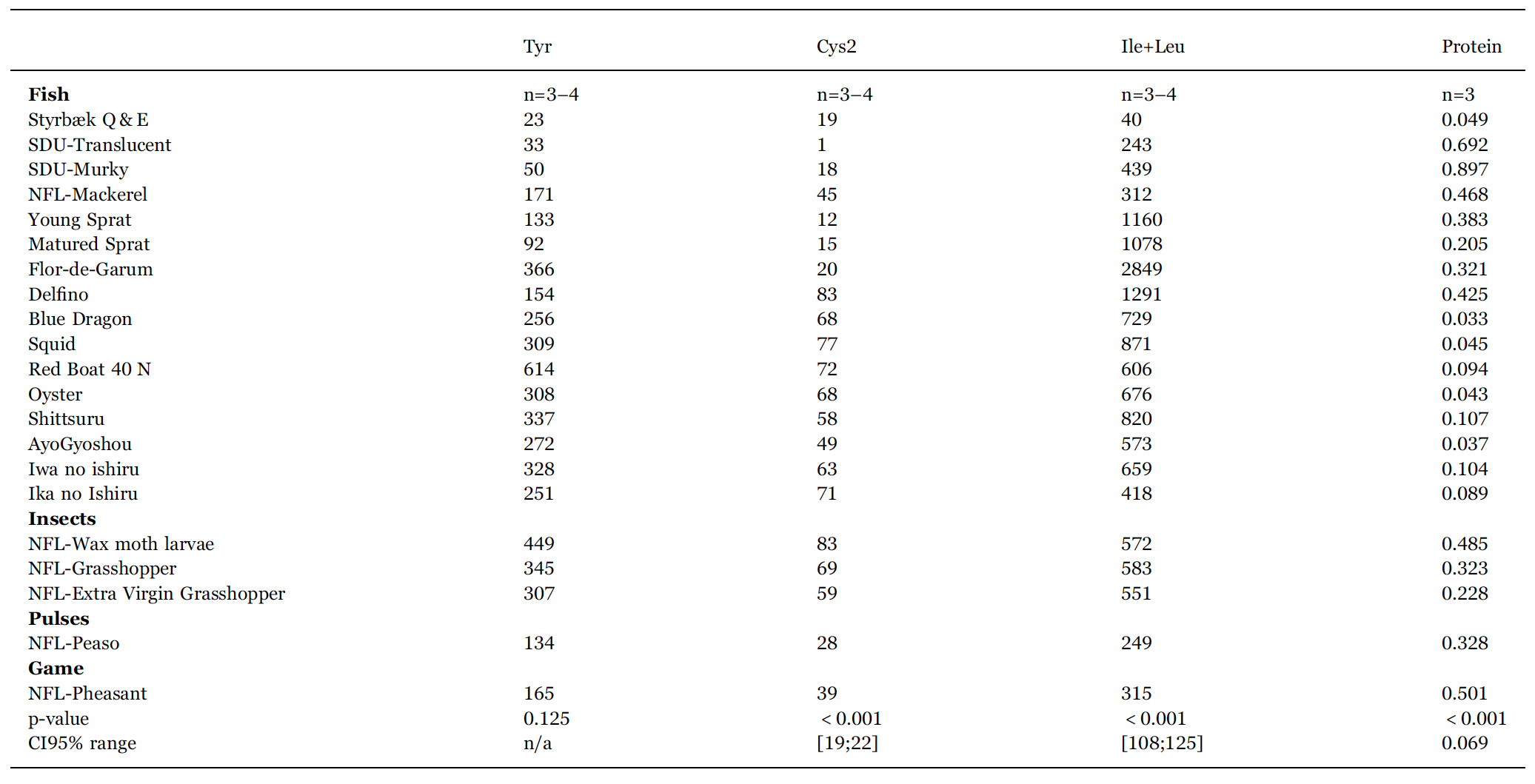

Mesmo em ambientes com menos salinidade como a salmoura, – ainda que com alto teor de sal 10-20% de NaCl – não é impedido o avanço dos processos autolíticos, mas é o suficiente para impedir o início da putrefação parando o desenvolvimento de microrganismos perigosos para a saúde.

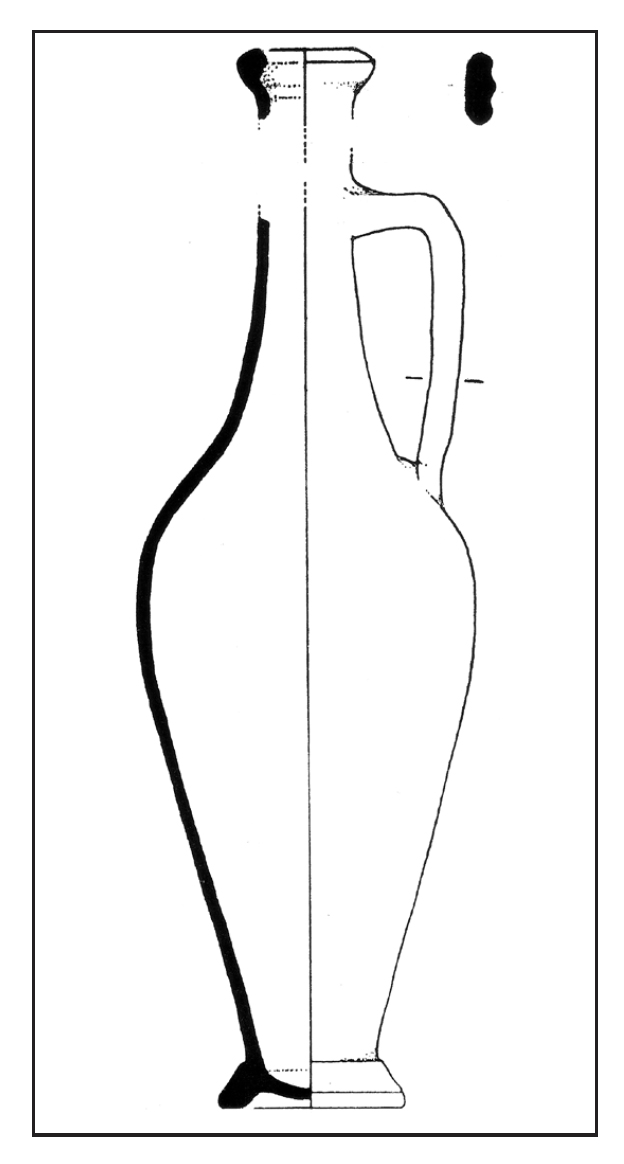

Passado algum tempo, o resultado da decomposição em salmoura leva à formação de um líquido perfeitamente comestível, muitas vezes de cor âmbar, salgado e cheio de proteínas, iodo e flúor, histidina e vitaminas A e D (lat. garum, liquamen). Também se obtem uma substância pastosa muito salgada (lat. allec) com excelente valor nutricional.

A outra parte invisível do processo de realização do Garum é a contribuição de micróbios, bactérias em particular. O microbioma humano é a soma de todos os microrganismos que residem nos tecidos e fluidos humanos e em cada local anatómico, a nossa boca, pele, sistema digestivo, possui o seu microbioma específico.

Os peixes têm também milhões de bactérias principalmente nas vísceras, muito mais do que os humanos na pele, porque a sua superfície é húmida. Existem assim milhões de enzimas por grama de peixe, especialmente no sistema digestivo e portanto muitas coisas vivas no tecido dos peixes mortos, enzimas que quebram proteínas e gorduras, para obter energia, alimentarem-se e reproduzirem-se.

No processo desse metabolismo, os micróbios geram os seus próprios conjuntos característicos de moléculas voláteis que são determinantes para o aroma do Garum. As enzimas dos músculos e as enzimas das vísceras – se o sistema digestivo for incluído na preparação do Garum – contribuem muito para a sua qualidade e sabor. São pois os micróbios que geram grande parte do aroma.

Pelo facto de os micróbios estarem envolvidos neste processo, é crucial que na produção sejam seguidos certos cuidados por forma a evitar a presença de micróbios patogênicos e que podem provocar doenças, como o botulismo. O botulismo pode resultar do crescimento de bactérias do género Clostridium, sendo controlado pelo uso do sal, pois estes micróbios não suportam altos níveis de salinidade.

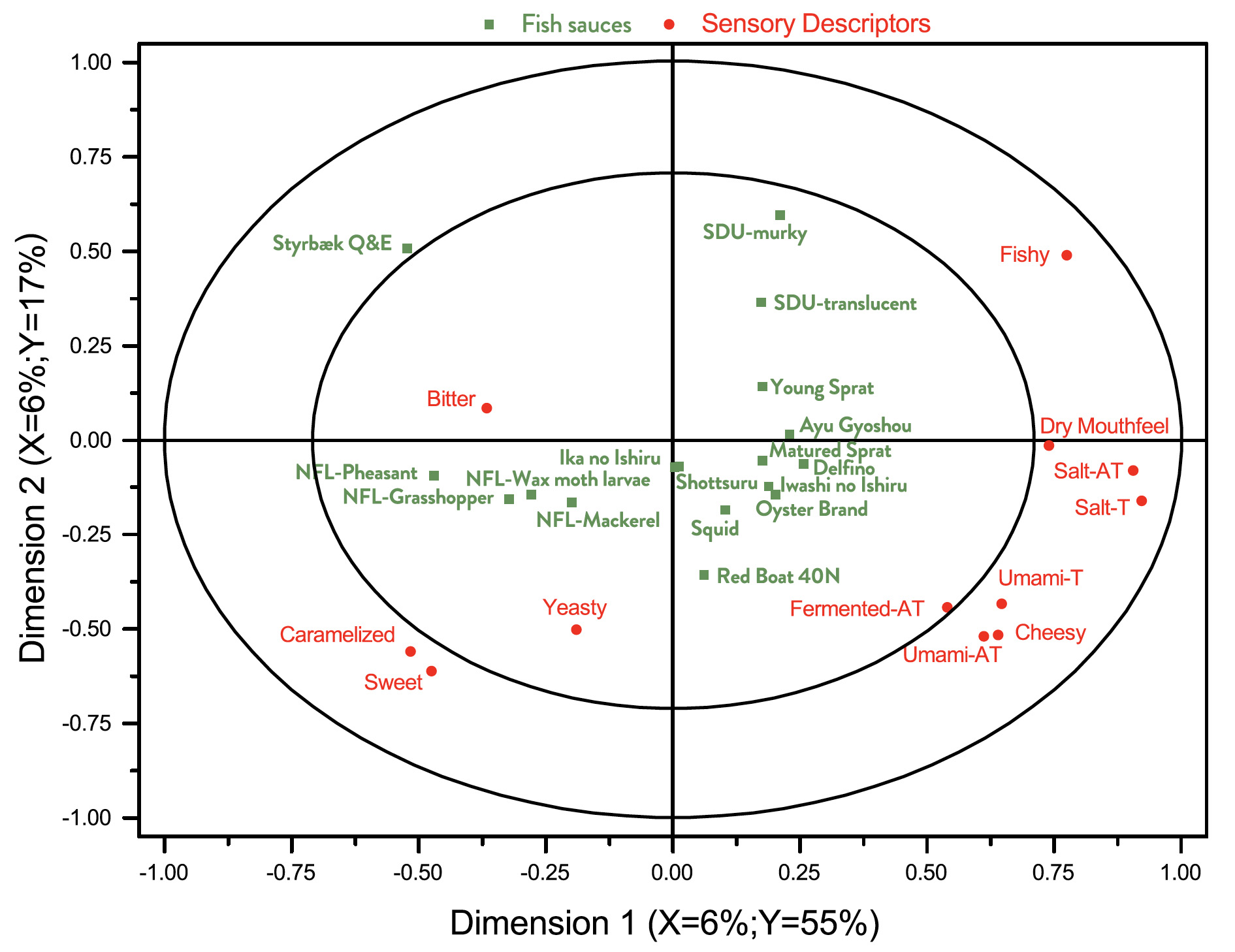

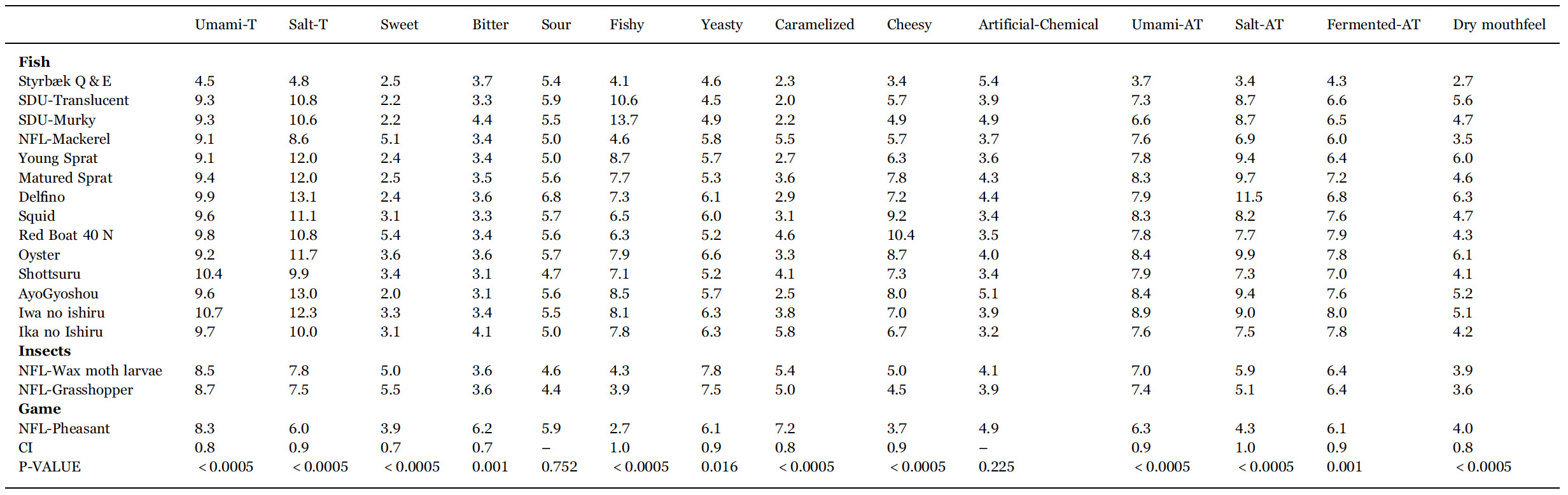

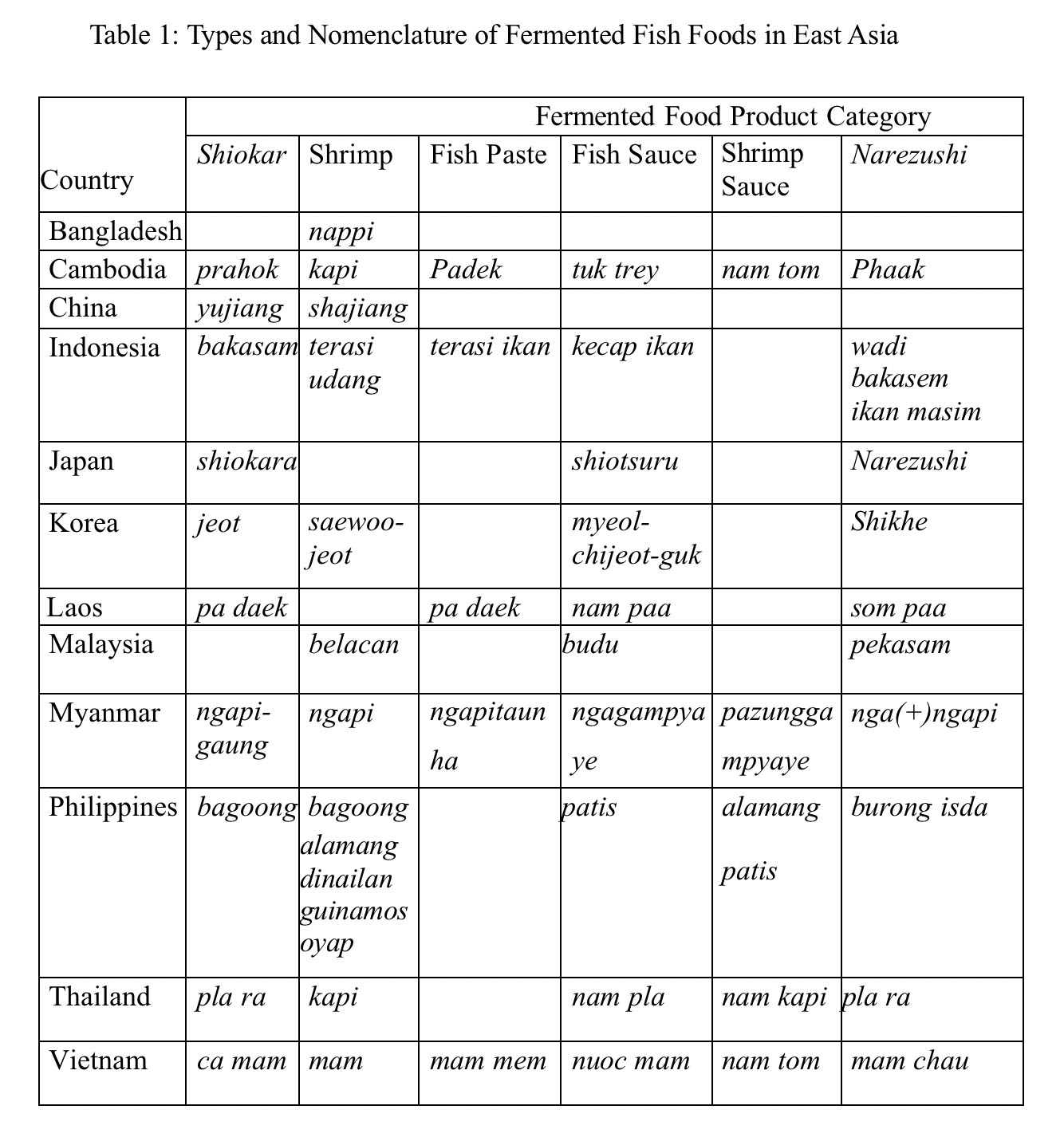

A produção de Garum é um sistema muito complexo, pelo que, diferentes tipos de molhos de peixe, feitos com diferentes processos, diferentes tipos de peixe, diferentes formas de produção, podem resultar em sabores também muito diferentes.

Elementos que influenciam o sabor do Garum

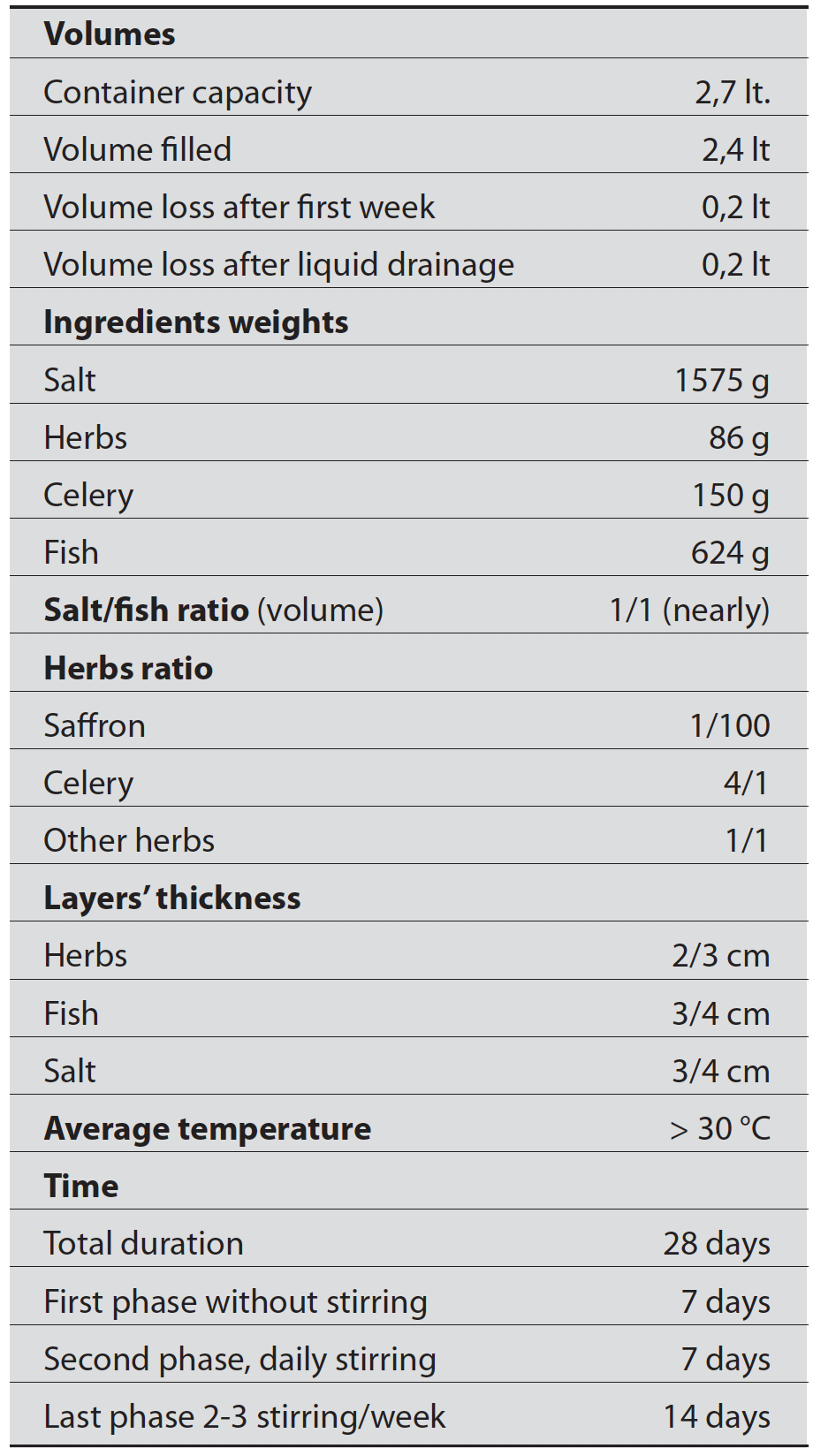

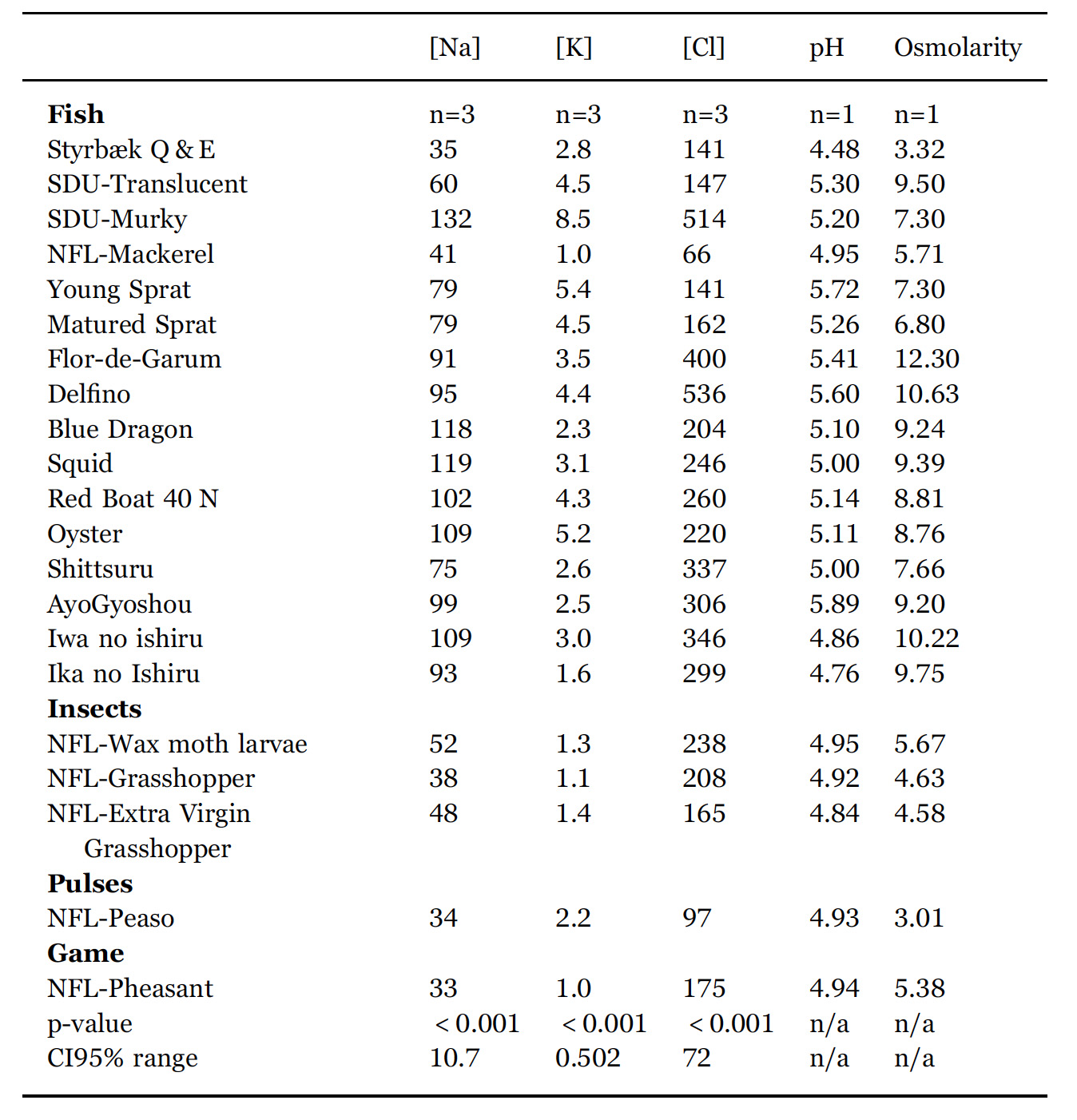

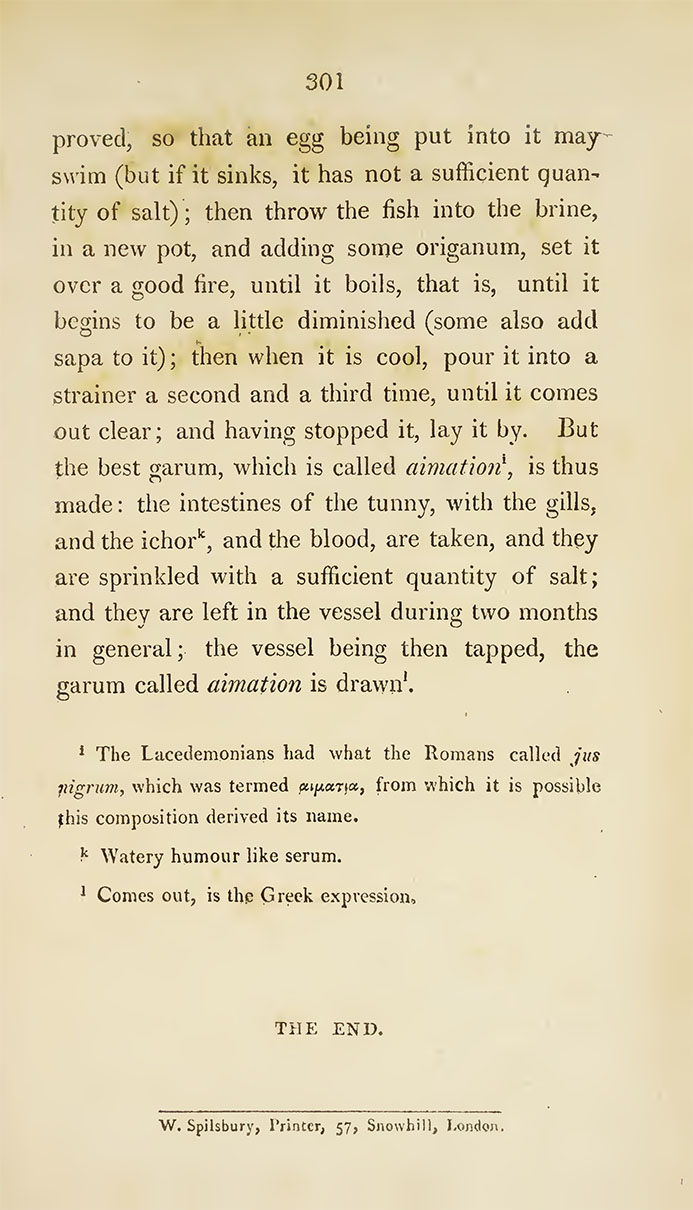

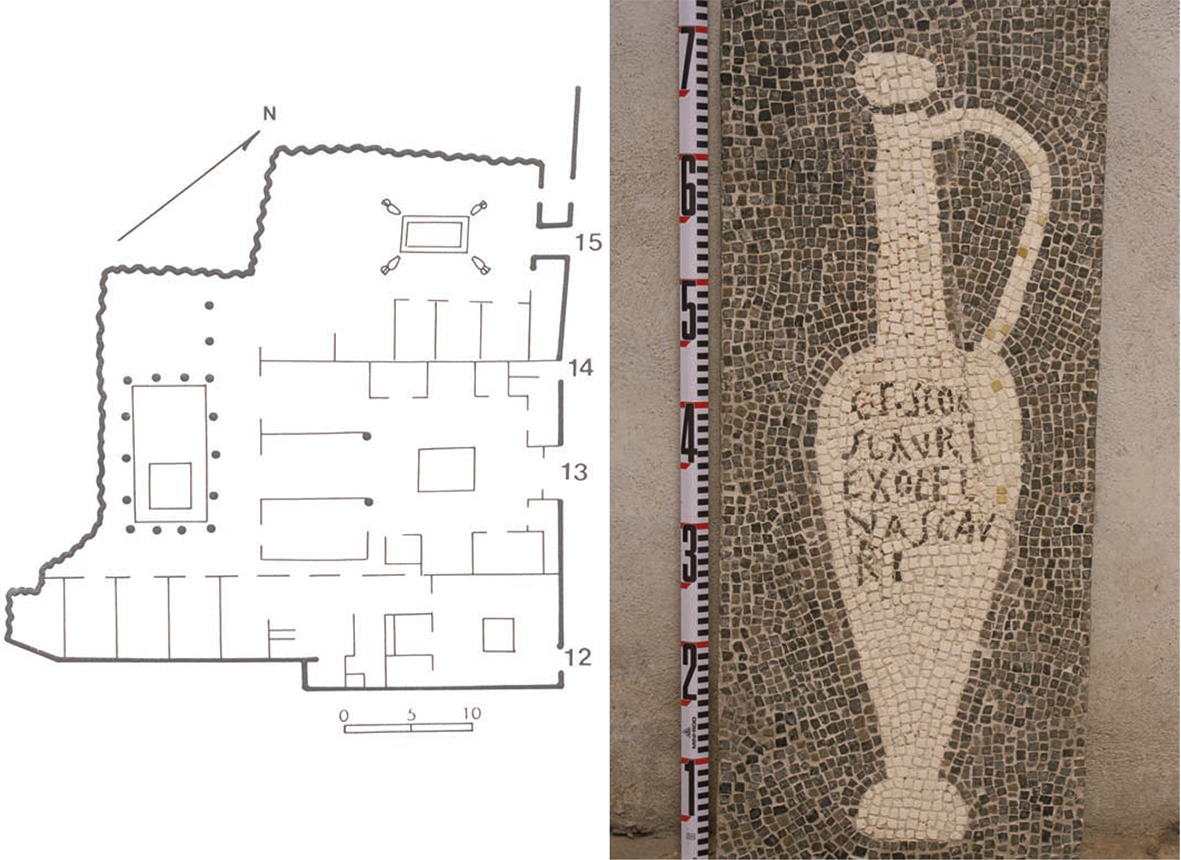

A espécie de peixe utilizada. Nesta produção de Garum em Tróia foi escolhida a utilização de sardinha. Em Tróia foram encontrados principalmente vestígios de sardinha, razão da escolha desta espécie para esta produção, além do simbolismo que a mesma representa para Portugal.

A água de onde provêm os peixes: a água é o lar das bactérias dos peixes. A sardinha utilizada foi pescada pela frota de pesca dos associados da cooperativa de pesca Sesibal, pescadas das águas de Setúbal e Sesimbra.

As partes do peixe que utilizamos: se usarmos as vísceras e o sangue, estamos a usar as enzimas digestivas, que são mais ativas do que as do músculo. Se utilizarmos sangue e fígado, estamos a adicionar muito ferro. O ferro é um catalisador para reações químicas que desenvolve sabores mais rapidamente e mais intensos.

O sal também influencia o Garum: no mediterrâneo é usado menos sal do que nos molhos de peixe da ásia. Utilizámos sal do último produtor activo do Vale do Sado, Carlos Bicha Lda, de Alcácer do Sal.

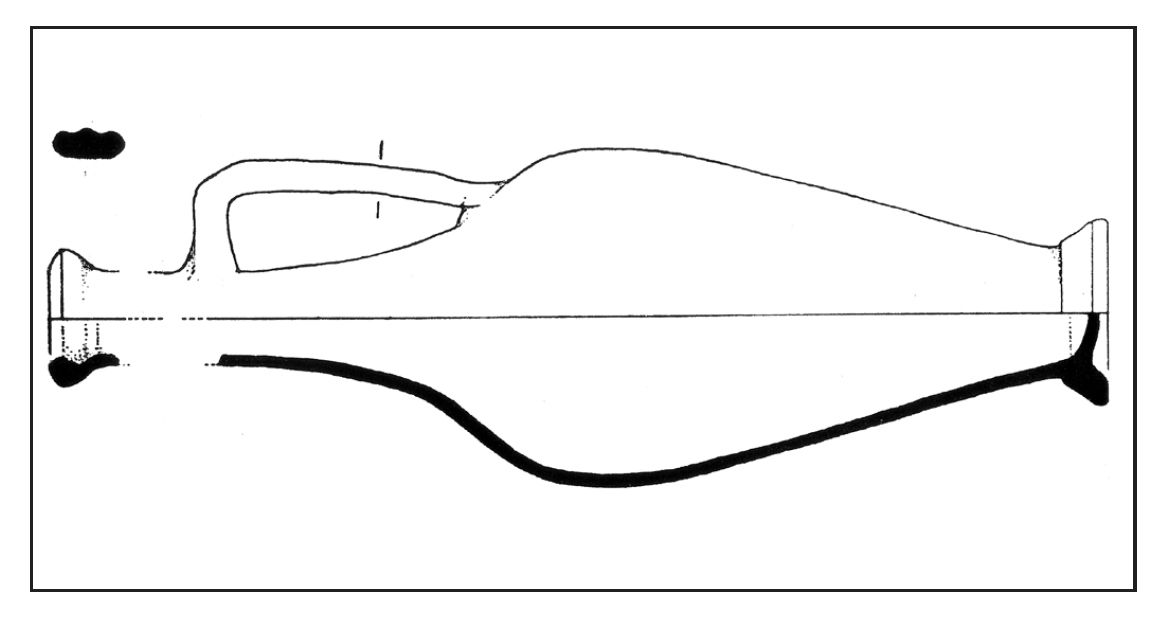

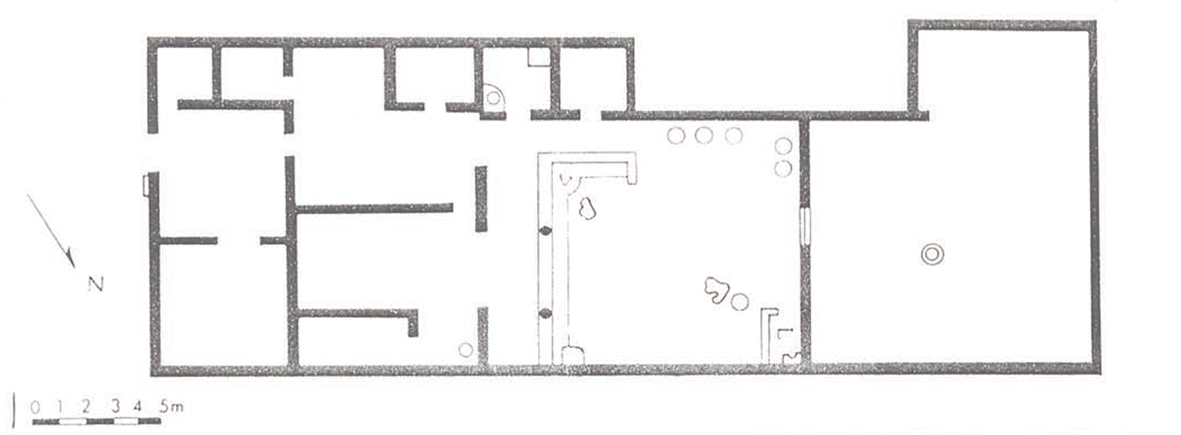

A temperatura de fermentação determinará que micróbios são capazes de sobreviver nestes altos níveis de sal e com que rapidez eles são capazes de trabalhar. Ao colocarmos o preparado de Garum dentro de uma cetária, irá fazer com este receba os calor das pardes de pedra, que aquecem durante o dia e emanam calor à noite.

A forma como se processa a fermentação, se parada ou agitada, se hermética, exposta ao ar, exposta ou não à luz solar, se é retificada a água ou se são adicionados ingredientes como grãos torrados, vinho, koji, um mundo de muitas possibilidades diferentes. A nossa fermentação é mexida semanalmente e não foram adicionados quaisquer ingredientes.

O período de fermentação. No caso presente calculamos que a fermentação até à conclusão do Garum não será inferior a três ou quatro meses, podendo demorar mais tempo.

O tempo de envelhecimento, que pode ser de vários meses, irá dar a essas pequenas moléculas desenvolvidas durante a fermentação, a chance de reagir entre si e gerar todo o tipo de coisas novas.

Supervisão técnica do texto: investigadoras na área alimentar Marisa Santos, Catarina Prista e Anabela Raymundo do Centro de Investigação em Agronomia, Alimentos, Ambiente e Paisagem do Instituto Superior de Agronomia