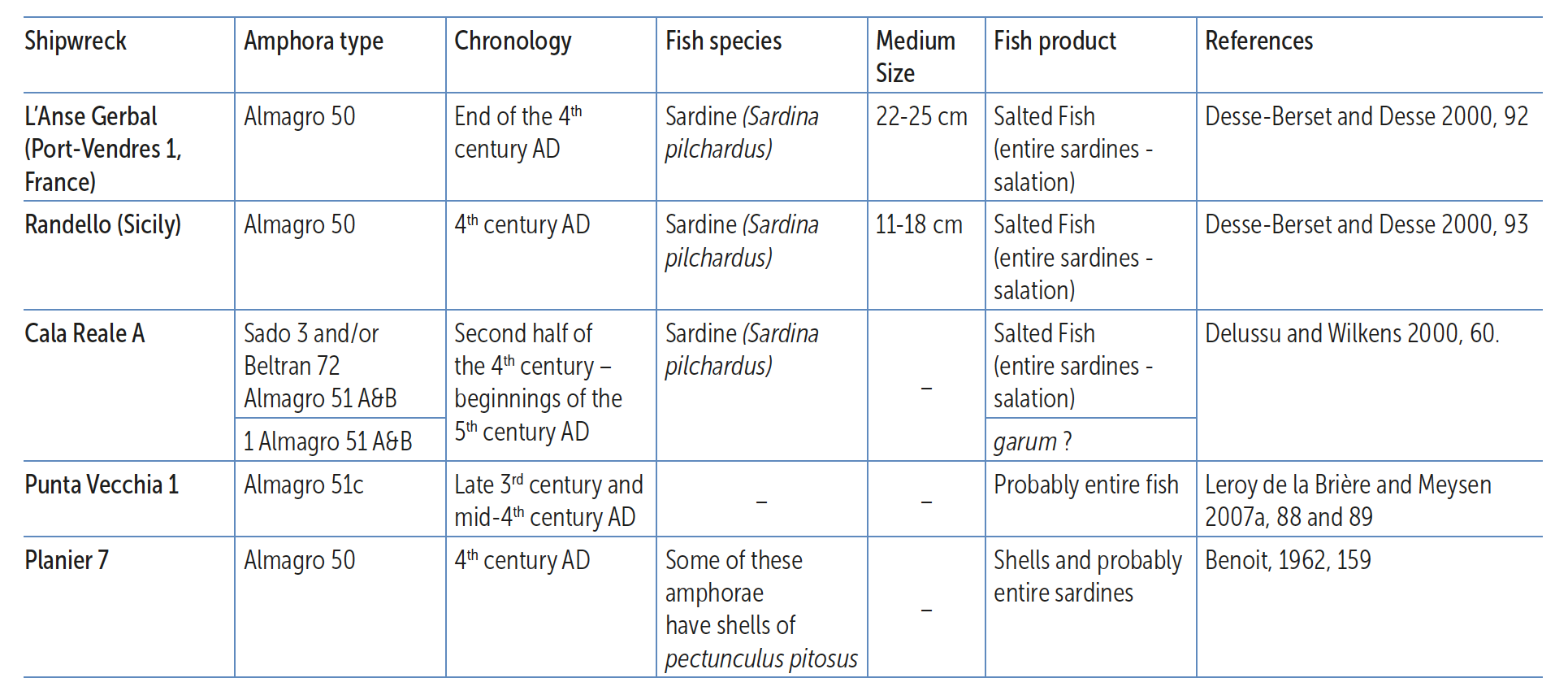

X. Garum, Liquamen, and muria: A new approach to the problem of definition

Sally Grainger

Introduction

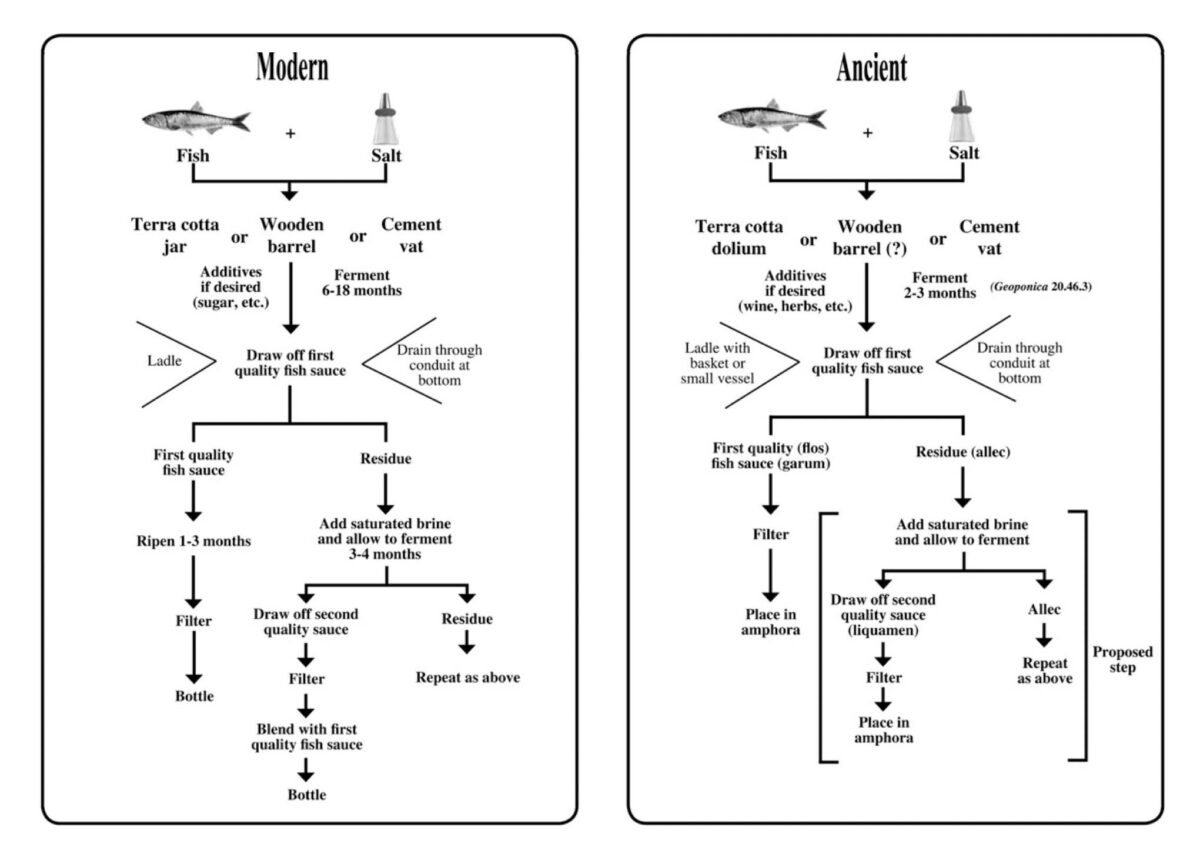

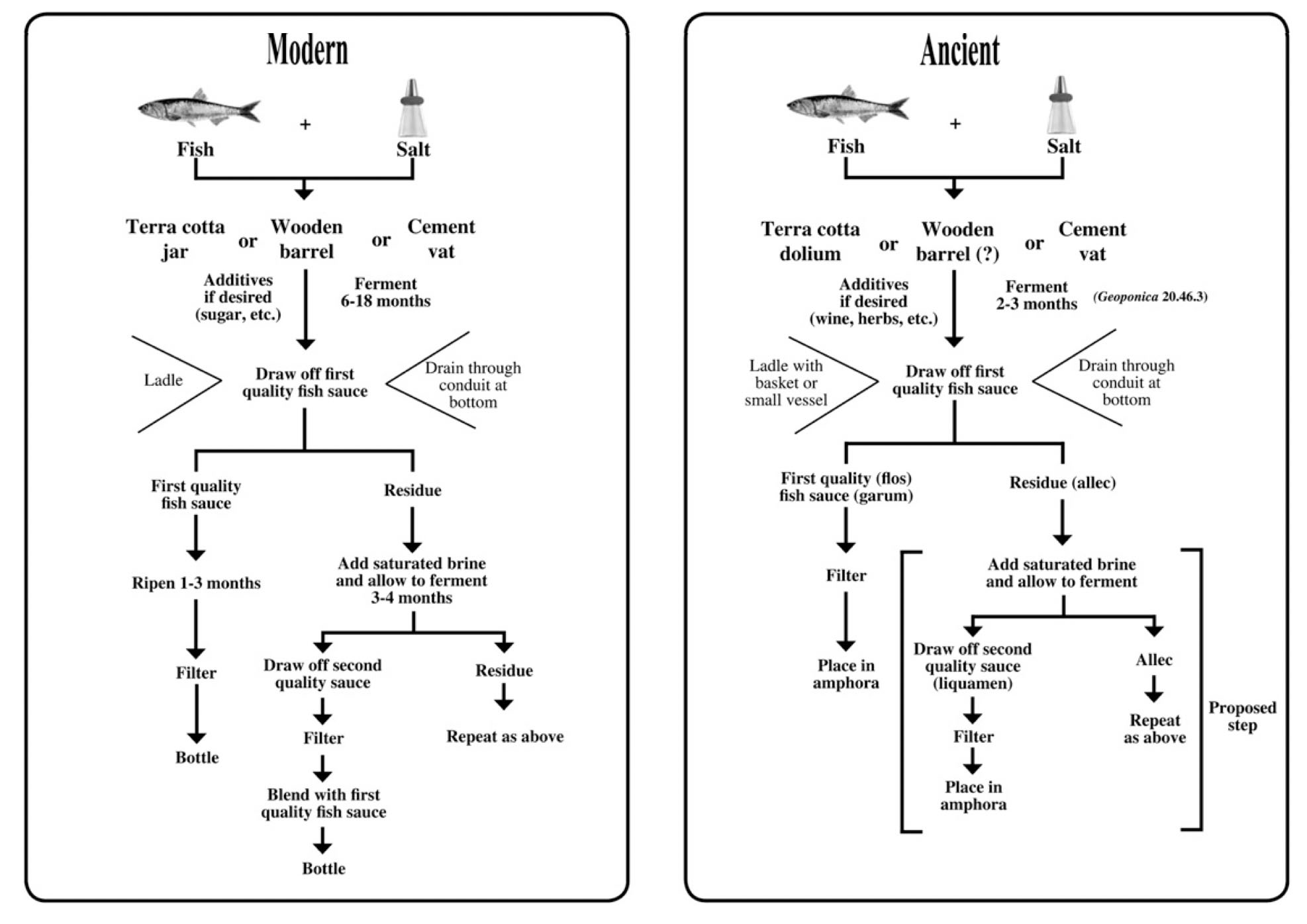

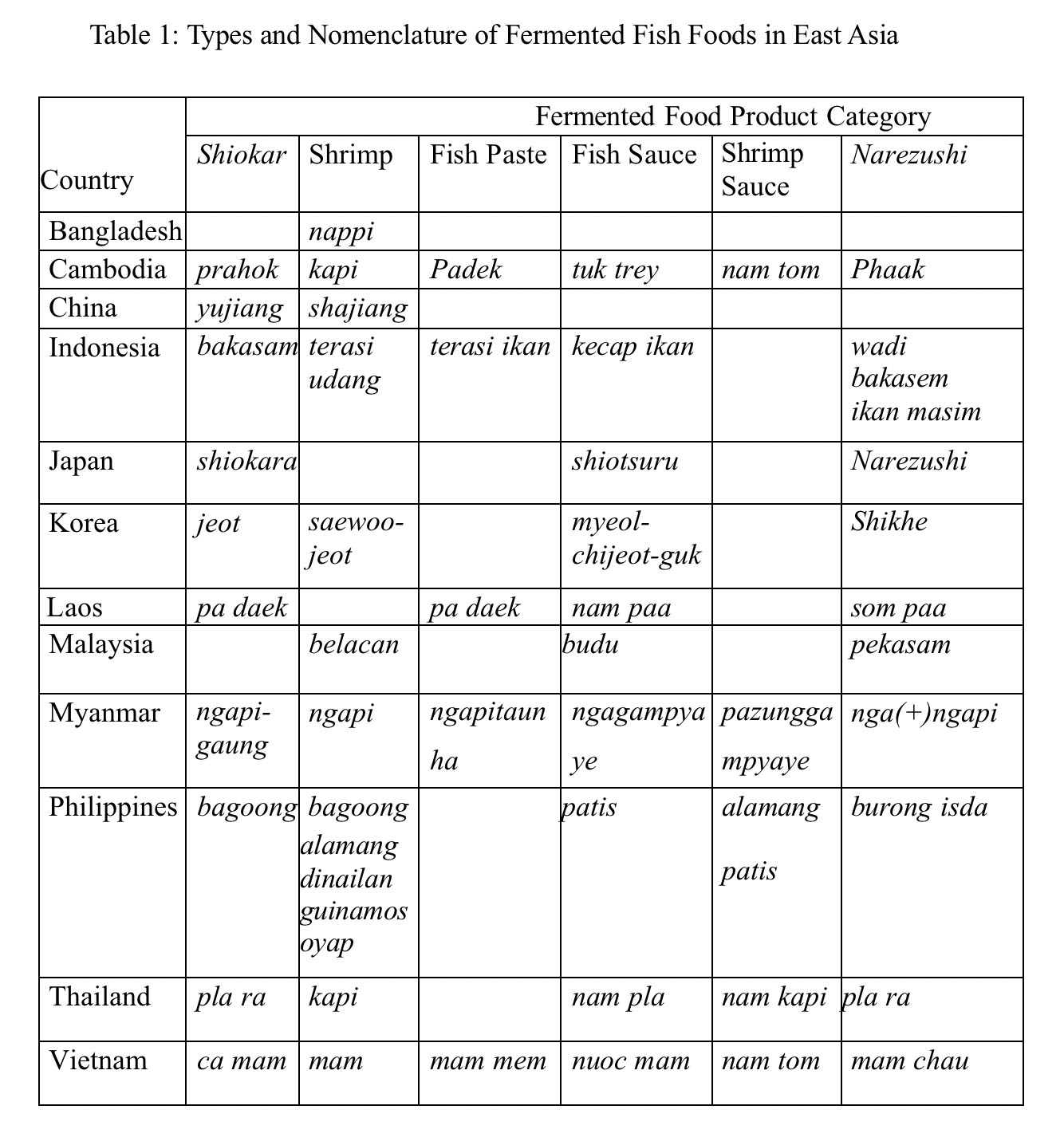

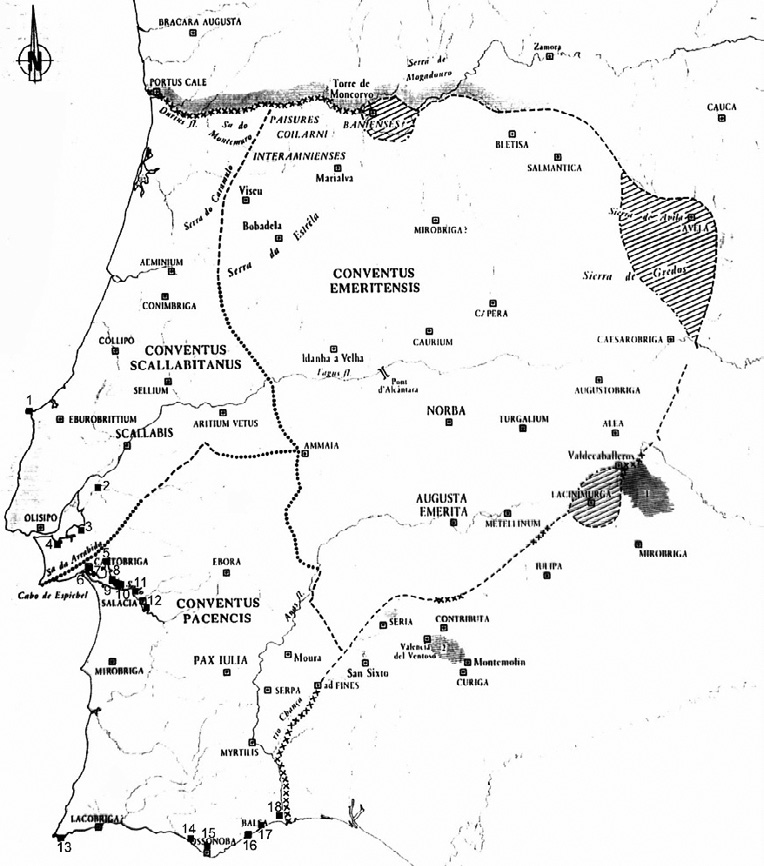

The picture of fish sauce that emerges from the ancient literature is complex. The ancient writers who discuss these products do so without the precision we need and often contradict each other so that a precise understanding of which sauce corresponds to which recipe, production process or name is less than clear. The ancient literary evidence is largely provided by two quite distinct kinds of text : on the one hand 1st c. AD elite Roman consumer perspectives from letters, Natural Histories, poetry and particularly satire, and on the other texts that are perceived as late-Roman from users such as cooks, doctors, and vets. These texts often derive from much earlier Greek sources so the evidence appears to be polarised both by time and by culture.

The early elite consumer tells us only of the exclusive and expensive types of garum which may have had quite a narrow culinary role and appear as the primary product, while the everyday cooking fish sauces used by millions of ordinary Romans and Greeks around the empire are hardly comprehended at all in the literature 1. In zooarchaeology we have the reverse situation, as the only recognised evidence for fish sauce is the bone fragments from small clupeidae and sparidae, which are identified as part of the apparently bony fish paste known as allec, the consumption of which is viewed as low status 2. This stark contrast in the perceived status of the consumer of each kind of evidence makes for confusing conclusions, such as the tendency for fish bone specialists to consider certain forms of this fish paste as an elite product with reference to the discussion in Pliny 3.

In the course of this study it will become clear that many ancient elite consumers of fish sauce did not actually understand the products at all well and it is their confusion that is directly responsible for ours. At the heart of this ancient and modern confusion is the failure on the part of modern researchers to comprehend fully that there were multiple varieties and qualities of fish sauce, some for cooking, some for the table, just as there are today in south east Asia. We can and must attempt to differentiate between them through a synthesis of the archaeological and literary sources. Only with this level of analysis can we hope to disentangle the complex problem of nomenclature. The ultimate aim is to gain a greater understanding of the relative value of the different fish sauces within in the ancient economy, and not least within Roman cuisine. In what follows I will offer a radically new way to approach the dilemma of how to differentiate between the various fish sauces which takes account of the opinions of those who made, traded and used these products.

1 Corcoran 1962, p. 205.

2 Van Neer 2002, p. 208.

3 Cotton 1996, p. 223-238. Pliny The Elder HN 31.96. « Allec is the sediment of garum, the dregs neither strained nor whole. It has, however begun to be made separately from tiny fish, otherwise of no use. The Romans call it apua, the Greeks aphye, because this tiny fish is bred out of rain… Then allex became a luxury and its various kinds have come to be innumerable… Thus allex has come to be made from oysters, sea urchins, sea anemones, and mullet »s liver and salt to be corrupted in numberless ways so as to suit all palates ». The Geoponica is very clear that the residue makes allec not that the entire residue is allec.

4 Corcoran 1963, p. 204-209 ; Curtis 1991, p. 13 ; Curtis 2009, p. 713 ; Studer 1994, p. 195 ; Etienne 2007, p. 7 ; Van Neer 2002, p. 208.

1. The single sauce hypothesis

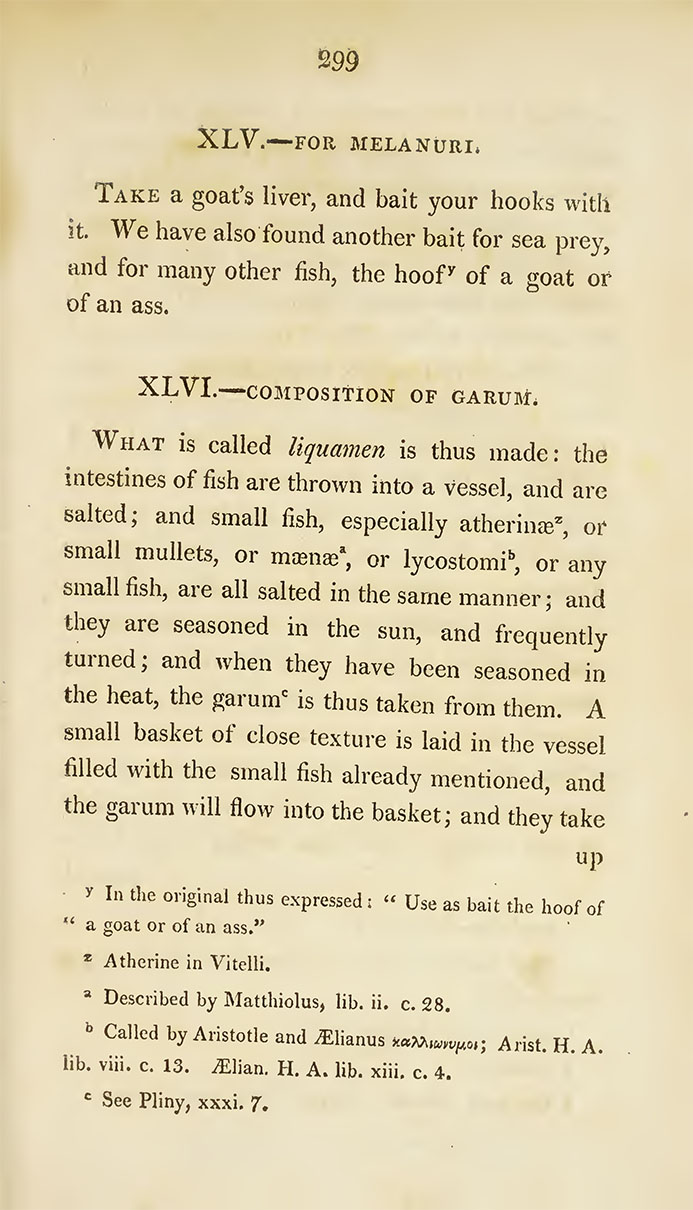

Within ancient historical and archaeological research there is currently an assumption that there was only one type of Roman fish sauce. This sauce was called garum ; all the varieties of fish, different components of fish, recipes and qualities were all defined within the generic term garum. The distinction between the fish sauce made from small and medium whole-fish with extra viscera and that made from just fish viscera and blood is acknowledged by the leading scholars in the field but they are all considered forms of garum 4. This belief stems largely from the statements on fish sauce by Pliny the Elder. Pliny’s garum is the luxury product made from fermented viscera and « other parts that would otherwise be considered refuse »(31.93). Pliny has stressed the viscera which is associated with the expensive sociorum garum and not directly referred to whole fish but his « other parts » have nonetheless been taken to mean small fish otherwise of no value : thus he seems to be referring to a whole-fish sauce not a blood/ viscera sauce. As he subsequently suggests that the residue of this garum makes allec and that this is a fish paste derived from whole fish, he must not comprehend that there were two types. The surviving Greek recipes for fish sauce also affirm the importance of the distinction between blood/viscera sauce and one made from whole fish. It is clear from the Geoponica too that the term garon, with an additional adjective to designate the blood/viscera sauce, did function generically in Greek 5. To make matters worse some ancient commentators, largely elite consumers, also seem to use the Latin term garum in a generic sense ; however it will be my contention that garum, for those who manufactured and traded these products, was a specific term in Latin referring to the blood/viscera sauce rather than a general term and that for most of the Roman period the word liquamen actually represented the primary product : a fish sauce made from whole-fish 6.

Manufacturer, trader and user didn’t use the word garum, as the elite writers seem to, as a term for the general idea of fish sauce in Latin, they employed a far more specific and technical terminology, which we may suppose involved precise use of all the terms at their disposal and which survives in ancient texts and on amphorae – in both Greek and Latin 7. There are a number of instances where fish sauce is described in term of colour. The blood/viscera sauce will necessarily be darker because of the blood and in fact we do find « black » and « bloody » adjectives being used in Greek texts 8. However in Latin the literary sources do not use specific adjectives with garum referring to colour. Instead we only find the singular garum, garum sociorum or liquamen. The use of the word sociorum « of our allies » we are told by Pliny refers to the luxury mackerel garum made in New Carthage in Spain. Martial describes this sauce being « made from the blood of a still breathing mackerel » and it therefore implies this black and bloody sauce 9. Whether we can say that all the sauce made by this company of allies in New Carthage was the luxury blood/viscera sauce is unclear and probably quite unlikely. The terminology used in the dining rooms of Rome may well have been different to those used by the manufacturer. Crucially we cannot know which sauce is being referred to when garum occurs singularly in Latin texts. Writers may not actually know or care which one they are referring to, especially in satire.

The meaning in Latin of liquamen has always remained obscure and has long been assumed to be a Late Latin equivalent for garum 10. Garum only appears in the early period, liquamen in the late and it is generally assumed that the word garum fell out of favour and liquamen simply became the more popular word. Not only has no one thought to question why this should be the case but no one has considered that multiple varieties of fish sauce require multiple terms in Latin and they do not seem to exist 11. If one looks closer at the literary evidence it becomes apparent that all the early elite Latin consumers refer to garum and there is no reference to liquamen at all. Liquamen is not a term used by elite/ educated Romans 12. Liquamen exists only in apparently late and vulgar Latin didactic literature such as veterinary and cookery books, which though considered to be written in the Late Empire, often can be seen to derive from much earlier Greek material 13. The situation is clearly more complex than a simple switch in terminology. It is admittedly clear that Latin garum is hardly mentioned in any forms of elite Latin literature after the mid 3rd c. AD, though the term does not disappear entirely as Ausonius makes an obscure reference to it in the early 4th c.14 We can also see parallel use of garum and liquamen in their occurrence on amphorae tituli picti from Rome and Pompeii in the 1st c. AD. That garum always meant something different to liquamen can be seen in its presence along side liquamen in the medicinal and veterinary and culinary texts 15. The employment of both terms suggests that garum had a meaning distinct from liquamen in the early period which was still current when the later fish sauce had apparently been renamed liquamen. Curtis acknowledges that liquamen must have had a separate meaning to garum in the first century AD but he maintains that it was the 2nd and subsequent washings of the residue of garum which is the only way to explain the later convergence of the terms 16. I would disagree here as the tituli picti do not suggest this and there is no evidence at all to this effect.

5 Geoponica 46. Dalby 2011, p. 348-349. The difference between the two sauces concerns the fish blood rather than viscera which, from my experiments, provide additional digestive enzymes rather than distinctive characteristics. The flavour of a liquamen made with and without extra viscera is indistinguishable and dominated by fish flavours while the blood sauce taste and smells quite distinctly of iron and is not fishy at all.

6 Curtis 1991,p. 7.

7 In Greek : garon, garou melanos,(black) : Galen, Kuhn 1965, p. 637. garon haimation (bloody) : Geoponica 20.46.6, Dalby 2011, p. 348-349 ; P. Anst. inv. no 44. In Latin garum, garum sociorum, gari nigri, garum flos, liquamen, liquamen flos, muria and allec.

8 For other ref. to gari nigri : Aetius 3,83 and Latin translations of Galen, see note 37. Pliny talks of garum blended to look like « aged honey wine » : Pliny HN 31.93.

9 Pliny HN 31.94 ; Martial 13.102, Curtis 1991 p. 8, n. 11.

10 In Greek liquamen is a hapax legominon appearing only in the Geoponica where it appears to be a direct translation of garon. For the standard view Etienne 2007, p. 7.

11 Curtis 2009, p. 713 ; Cotton, Lernau and Goren 1996, p. 231.

12 It is cited in Columella three times at 6.2.7 ; 9.14.3 and 9.14.17 but each time liquid generally are meant.

13 Grocock and Grainger 2006, p. 13-23, 61 ; Adams 1995, p. 663. Much of Pelagonius and Vegetius is derived from writers such as Celsius, Columella and Apsyrtus : the Greek horse doctor.

14 Ausonius Epist 25. 21.

2. Studies on fish sauces

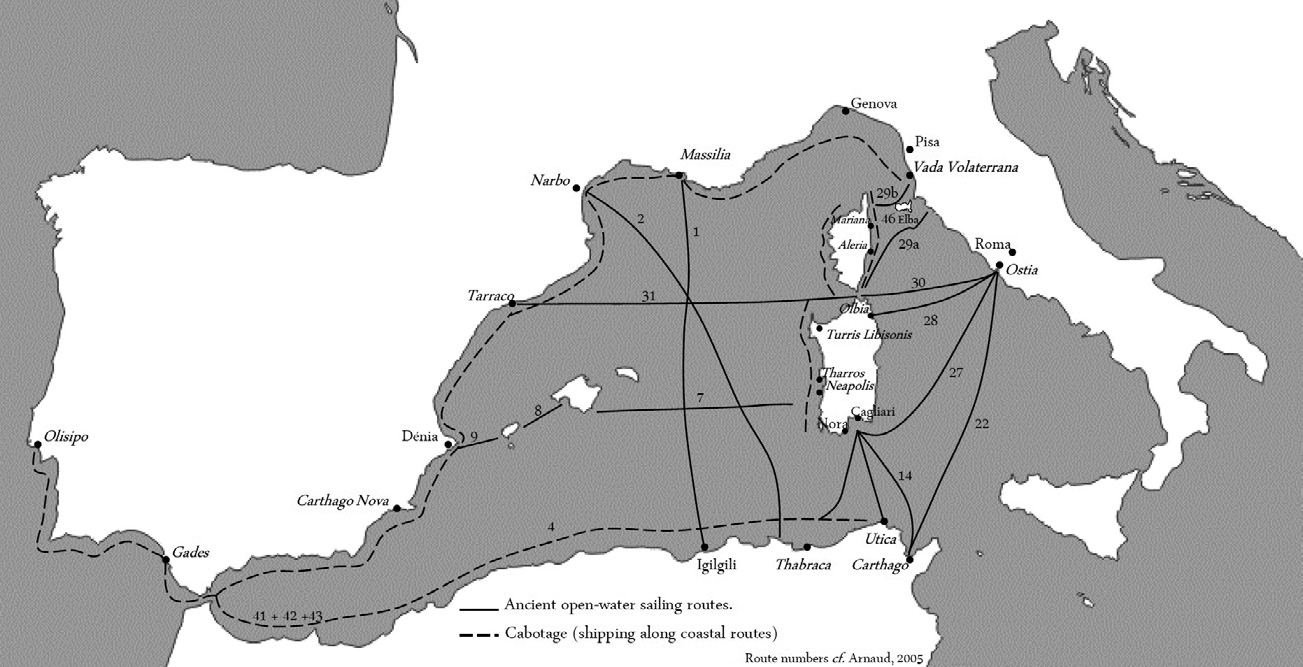

2.1. The origins of fish sauce in the Mediterranean

Garum was clearly derived from the original Greek word garos and seems to have been the name of a fish used to make the sauce in Greece according to Pliny. This fish is unknown but we may reliably assume that it was small clupeidae and sparidae. We know that 5th c. BC Greek comedy refers to garos from the Black Sea and by the 4th c. Cadiz was shipping garos to Athens 17. We know very little about this early fish sauce apart from the fact that it was considered rotten. Crucially the image of fish sauce use from the early Greek sources never appeared to have a luxury tag : the foods it was associated with were simple poor man’s vegetables and pulses and it formed a very basic dressing or dipping liquid with oil and vinegar or wine 18. The formal Greek cuisine that emerged during the Hellenistic period seems to have been defined around the use of this garos and it is this cuisine that arrived in Rome in the 2nd century BC when the Roman elite fell under the spell of Greek dinning culture 19. At this point we must assume that this garos was made from small fish, otherwise of no value, and the term simply became latinised into garum. At this early period we seem to be dealing with a single sauce of the whole fish garos type.

However the cuisine associated with elite dining as described by Archestratus in the late 4th c. BC in Sicily does not appear to use a garos fish sauce, despite its apparent importation into Athens at this time, but does make use of a similar dipping sauce blended with vinegar and oil made with a salted fish « brine » called αλμη (almē) 20. If Archestratus reflects elite practices a century before the Romans acquired a liking for Greek dining practices then the use of halme and its Latin counterpart muria would seem to be the more elite product and the knowledge and use of it would also be widespread. There was clearly more than one type of fish sauce at the end of the Hellenistic period. Garos and muria were sufficiently different to require separate names though whether the blood/viscera garum had yet been developed is not clear.

2.2. Apicius : the Roman recipe collection

The text where we find fish sauce in use most often is the recipes collection known simply as Apicius. In 2006 I along with Dr Christopher Grocock published a new edition of this text 21. The text had been interpreted by Brandt to be a collection of recipes written down if not actually compiled by an elite gourmet in the late Empire 22. This was due to the use of vulgar Latin which is the literary register most common in the late Empire among the elite as well as the rest of society. However it was clear to us that the individual recipes had actually been written by the slave cooks who would speak and write their own « blue collar » Latin. The Latin was grammatically inferior and displayed no literary merit of any kind. Brandt’s imaginary compiler is also absolutely silent : there is no authorial voice in the text at all and one would expect an author/compiler to make himself known. The silent compiler suggested to us that this text was actually a functional collection designed by and for the cooks who devised and used the recipes. This conclusion has repercussions for dating the text too as it may be concluded that any vulgar/late Latin written by an elite gourmet would date the text to the late 4/5th c. AD but vulgar Latin from cooks cannot be so precisely dated : « Vulgar Latin…is just a collective label to refer to all those features of the Latin language that are known to have existed from textual attestations and incontrovertible reconstructions, but that were not recommended by the grammarians » 23. It is quite clear that a grammatically inferior written Latin co-existed with the more learned registers in 1st century imperial Rome and there is no reason why many of the recipes could not have been written down at that time. In fact some of the recipes contain internal evidence to suggest that they were originally written down as early as the 1st c. AD 24. We may also suppose therefore that many of these recipe collections, of which Apicius is just one surviving version, began the process of compilation in the early empire and under particular Greek influence as the surviving recipe collection retains its Greek chapter headings and contains numerous technical culinary terms which are hybrid Greek/Latin terms 25.

15 For Apicius see below. Pelagonius liquamen : 9 ; 11.2 ; 13 ; 98 ; 455 ; 457, garum : 428;13. Vegetius liquamen : 1.10.1 ; 1.17.10, 16 ; 2.91.2 ; 2.108.2 ; 2.132.4 ; 4.6.1, garum : 2.28.8 ; 3.28.10. Marcellus Empiricus, 5th c. medical writer from Gaul « Medicinae » liquamen 30.52 ; garum 30.41.

16 Curtis 2009, p. 713. Ausonius Epis.t 21.

17 Pliny HN.31.93. Dalby 1996, p. 75-76 ; Athenaeus, II, 67.b-c.

18 Dalby 1996, p. 25 Galen On the properties of food 1.25.2.

19 Grocock, Grainger 2006, p. 17.

20 Olson, Sens 2000, p. 159 (fr. 38). Athenaeus VII, 329b : where the brine is identified as from pilchard.

21 Grocock, Grainger 2006.

22 Brandt 1927, p. 30, 36, 130-3.

23 Herman 2000, foreward ; Grocock, Grainger 2006, p. 95 and note 1.

In relation to the issue of fish sauce terminology these conclusions have profound consequences. There is very little garum qua blood garum in Apicius : in these recipes the cook does not appear to use this sauce and in fact we have no reference to cooking with the blood/viscera sauce anywhere in the literary evidence. This would seem entirely logical too, as an expensive and intensely- flavoured blood sauce would be lost in the cooking process and wasted, while an expensive sauce needed to be seen by the gourmet to be experienced, valued and discussed. In Apicius, liquamen is the universal term for the primary fish sauce and even when we find garum, with two exceptions, it is part of a compound term directly transliterated from the Greek : όıνογαρον (oenogaron = oenogarum) and therefore referring to the original whole fish sauce. In Apicius oenogarum is a slightly more complex version of the Greek wine/ vinegar, oil and fish sauce dressing 26. These sauces are widespread throughout the text and represents a hot or cold, thin or thickened sauce used both within a cooked dish and served as a dip 27. When the recipes themselves were firmly dated to the late empire, the use of liquamen to designate the « single » fish sauce was at least rational. Now the recipes do not necessarily fit neatly into that early/late pattern, the lack of black garum in Apicius is striking. Apicius is supposed to be the epitome of high status cooking and black garum is the luxury sauce par excellence, so why is it barely mentioned ?

From modern South East Asian cuisine we learn of a fermented squid blood viscera (and ink) sauce that is used today in Japanese cuisine. It is known as ishiri and is used as a finishing sauce for sushi as well as cooked food. Its taste neither fishy nor salty, and smells of the iron compounds from the blood. Japanese cuisine also has a whole-fish sauce called ishiru and many dishes are prepared with both i.e the whole fish sauce is used for cooking and the blood/viscera sauce finishes the dish 28.

I would suggest that black garum was never part of the cooking process and its absence perfectly natural in both early and late recipes. It was too strong for cooking and was designed to be used at table by slaves or diners as a « finishing » sauce. It became popular among the elite to blend oenogarum sauces with black garum in the 1st c., but by the time the recipe collections had been finalised in the 4/5th c. its use in this way was limited. In Apicius garum occurs just twice : as a non compounded word, it is found at 7.13.1 where mushroom are served with garum and pepper : « Ash tree fungi : boil and serve while hot and dry in garum and pepper, as long as you pound the pepper with liquamen ». The recipe is of course ambiguous and we might use it to retain the current belief in the « single sauce ». However taken literarily the pepper is pounded into a mash with liquamen and then the mushroom are served with this mash and blood garum 29.

2.3. Garum and Diocletian’s Price Edict

The single sauce hypothesis is reinforced by the wording for fish sauce on Diocletian’s price edict. The inscription is a controversial source for many reasons which are not of concern here 30. Dated to AD 301 it lists the prices, in Greek for the eastern Empire and Latin for the west, of common commodities and services available when inflation was very high throughout the empire. We find that in Latin 1st and 2nd quality liquamen is rendered as 1st and 2nd quality garos in the Greek inscriptions 31. This is however what we should expect : the primary product of trade and commerce was liquamen and it corresponds to the original primary product from Greece. It is more surprising to find that a separate blood/viscera sauce or a muria is not listed. I would argue that the rarity of black garum in texts in the late empire, particularly in Apicius, reflects a rarity in commerce too and that it was not sufficiently popular at the time of the edict to warrant its own price. It was clearly commercially available as Ausonius’ letter confirms but may simply have been such a small percentage of the overall market that it didn’t warrant its own listing. It is possible that black garum always had a relatively small market in comparison to liquamen and lost what popularity it had in the late empire. I believe black garum was made to appear more important because of the unusually close view we get of the elite at table in the early empire through satire. The obsession in luxury foods in dining was largely concentrated in the early empire and later Romans looked on their ancestors

24 Grocock, Grainger 2006, p. 13-23 ; 369-372.

25 Oenogarum, oxygarum, hypotrimma, tisane, thermospodium, oxyporium, melizomum : Grocock, Grainger 2006, p. 27.

26 Dalby 1996, p. 25. Other compound sauce were oxygarum with vinegar ; hydrogarum which is a cooking liquor not a sauce per se ; garelaeum with oil (Orebasius 4.28).

27 A sauce poured over a dish (4.5.3 ; 8.8.7) ; a salad dressing for vegetables (passim book 4) ; a sauce used within a dish (4.5.1 ; 4.2.31 ; 4.2.5) and a dressing for fish or meat (7.3.1 ; 10.3.11,12). A translation for the word oenogaron is found in a late gloss to the Gargilius Martialis text. This text provides the other important recipe for fish sauce manufacture and the sauce is entitled « Confectio liquaminis, quod oenogarum vocant » « a liquamen sauce which is called an oenogarum.

28 http://www.ishiri.jp/en/ This sauce is truly fermented with bacteria and low salt. It is quite remarkable that the Japanese word for viscera is gari !

29 For a similar pepper mash : Apicius 2.2.8. Vegetarian version of these fish sauces existed it seems and the terminology used is indicative of the primacy of liquamen/garos. Pseudo-Pollux Quotid. 112v : a text with Greek and Latin has « with a garos of turnip » is equivalent to « with a liquamine » ; Palladius Opus Agri. 3.25.12 « Liquamine ex piris » ; Pseudo-Galen De Remediis vol 14, p. 546m.

30 Lauffer 1971, p. 124.

31 Id., p. 104.

2.4. The uses of black garum

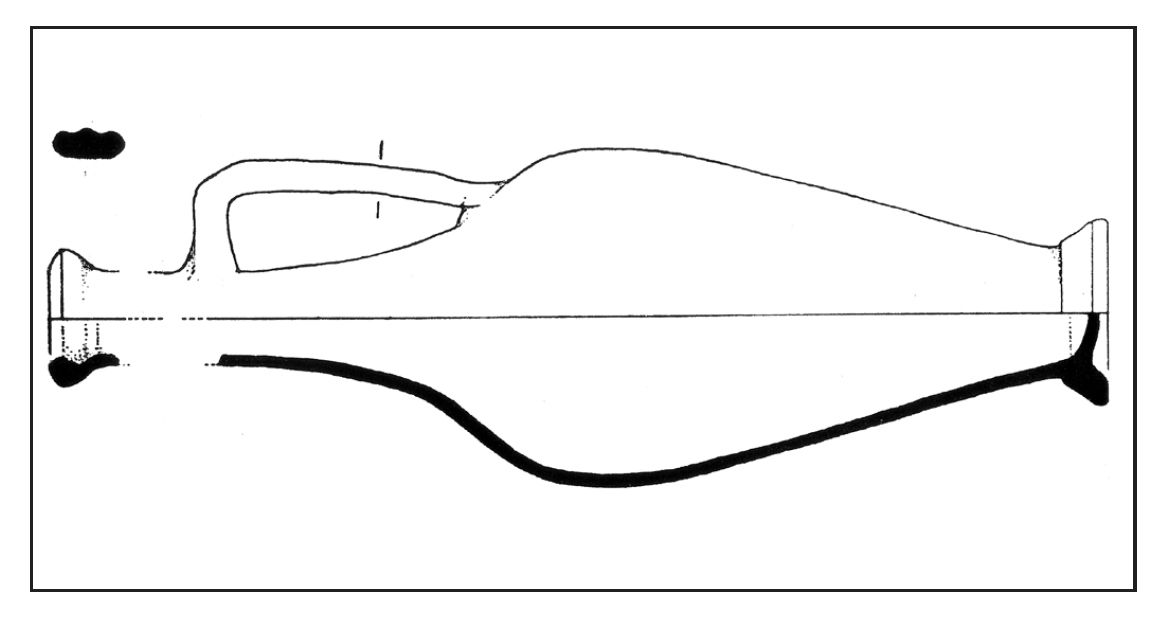

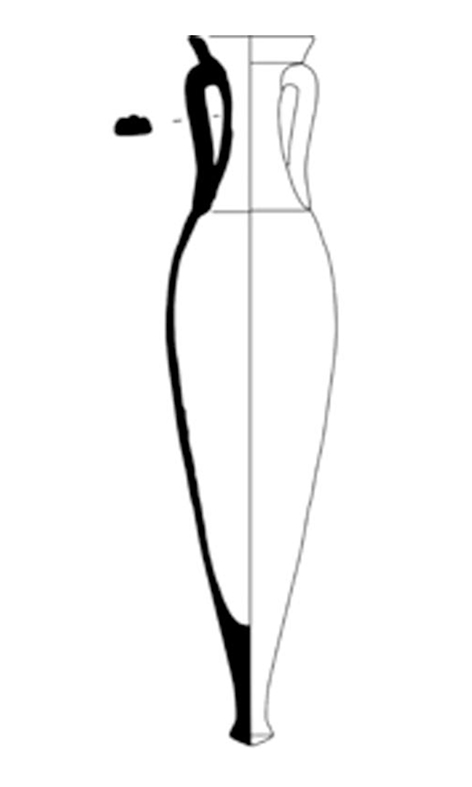

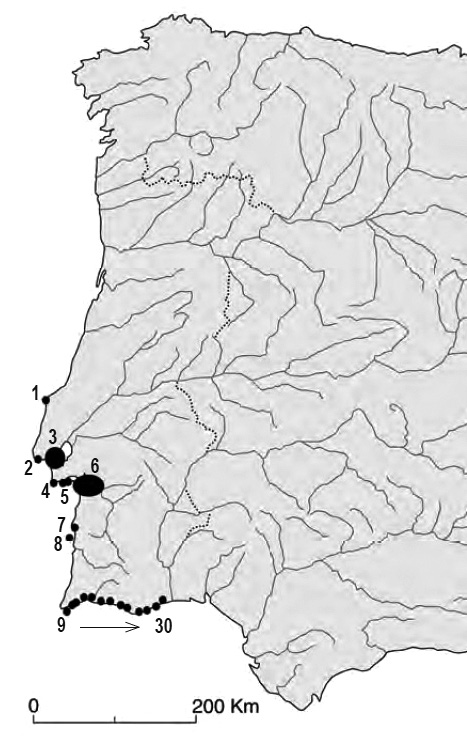

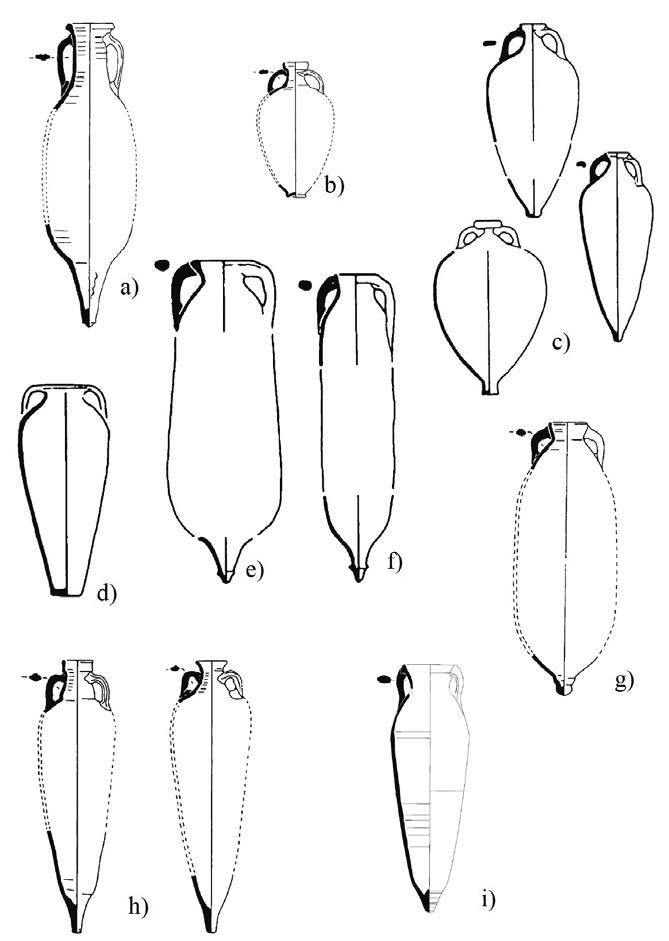

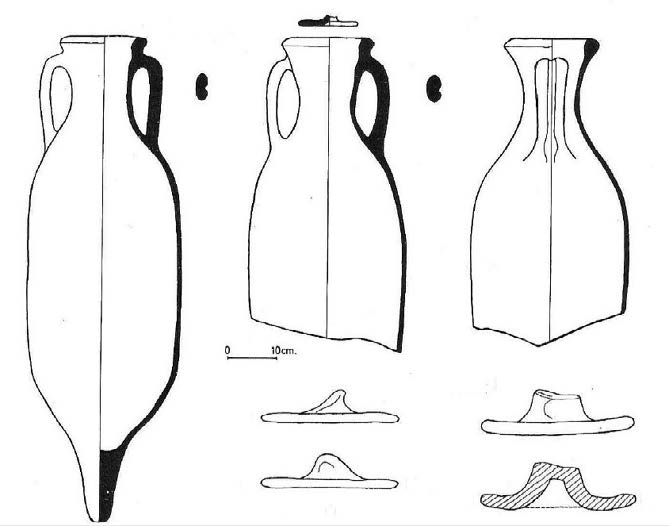

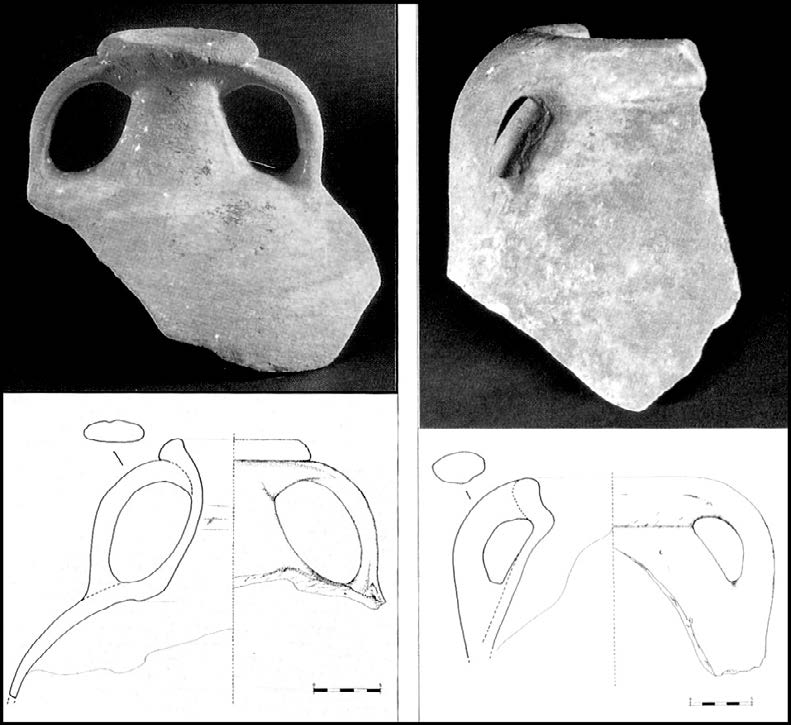

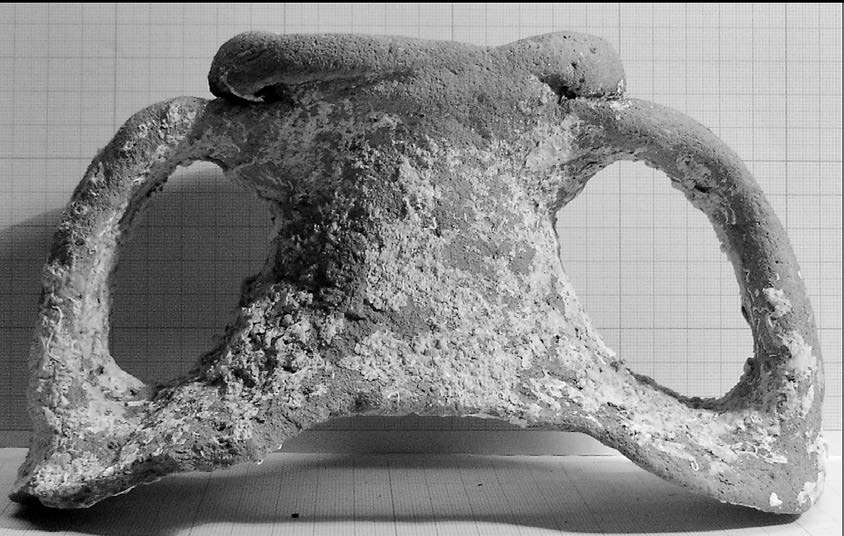

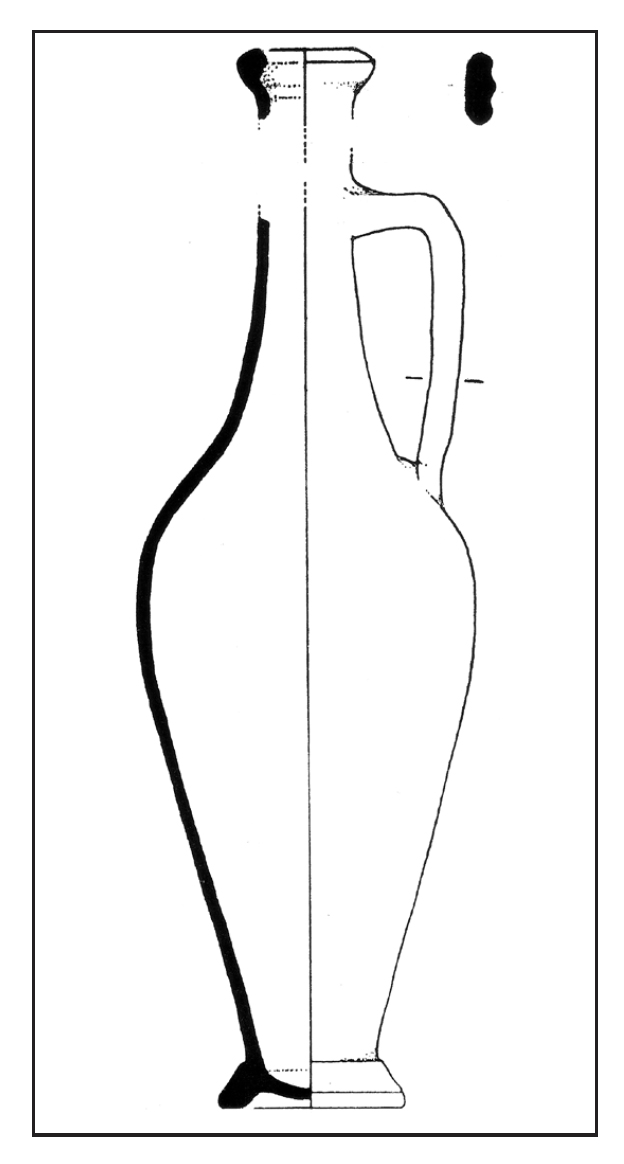

If we look elsewhere at the references to garum in satire it becomes clear that the sauce being discussed is a visible thing as opposed to being hidden away in the kitchen. That the term liquamen is unrecognised by the gourmet is not surprising given that the « cooking sauce » would never be visible. We find garum poured onto oysters ; Ausonius when discussing the garum he has received says he will « fill my patina » with it : a patina is a thick set frittata delivered cooked from the kitchen ; fish is served as if floating in garum ; a garum piperatum pepper sauce is poured on to fish in a dish from a wine skin ; a garum sociorum made from mullet viscera is used to drown and serve with mullets while an allec is made from their livers ; a cook is expected to blend Falernian with aged garum and pepper to serve with a roasted boar ; a cheap mistress begs her lover for a small amount of garum ; Garum and in fact muria too is used to make special oenogarum sauces and the host discusses the ingredients being used in such detail that we may be able to say that these sauces were blended at table 33. Certainly finely decorated Samian wear mortaria are often found with wear pattern of use and this is difficult for archaeologists to comprehend as they are assumed to be table ware. Most mortaria are course kitchen wear vessels and the labour involved in their use would normally be hidden 34. It may be said that there are too few references indicating that blood garum was always used in different ways to liquamen. It is also apparent that all three types of sauce (muria, garum, liquamen) could be blended with wine and oil to make the dipping sauce oenogarum which was a visible component of ancient cuisine yet it seems clear from the recipes that the black sauce was not used in cooking. It may be possible to determine the quantities of garum to liquamen consumed through analysis of amphora size. The urceii or table top jugs that fish sauce was sold in at Pompeii came in many sizes (fig. 1).

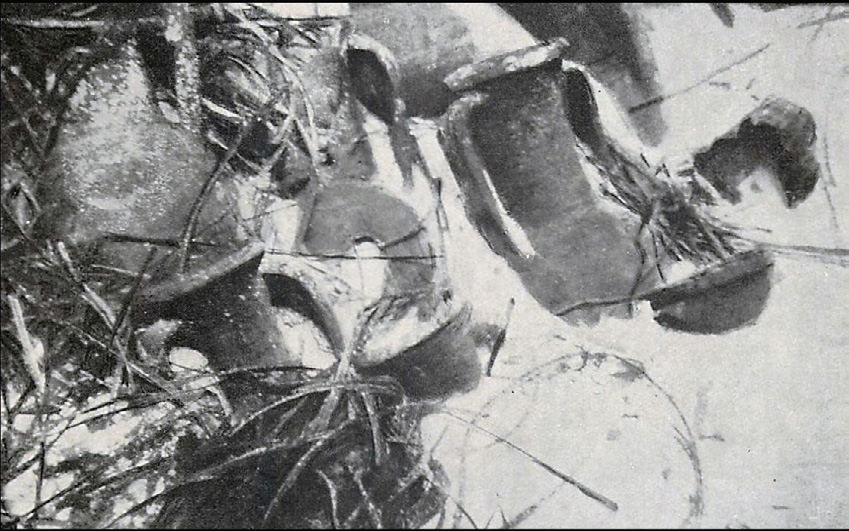

All are very much smaller then the average fish sauce amphorae which can stand up to 90 cm. From published tituli picti in CIL, the majority of liquamen labels are on amphorae, while named and exclusive garum is largely found on the much smaller urceii. Curtis has also noted that these urceii labelled simply garum have been found in Pompeii in relatively modest dwellings and bars and, though he was at the time using garum to mean fish sauce generally, this must mean that black garum was also consumed among the sub-elites probably as a table sauce in the bars 35.

Urceus found in Terzigno near Pompeii (from Cicirelli 1996, fig. 10-41 p. 166).

32 Ausonius’ text is discussed in detail below. While living in Southern Gaul in the 4th c. he had to have his garum specially delivered. Macrobius a century or so later « not that I am saying we should be though superior to the ancients…. but I am just stating the facts : people were keener on luxuries in those days than they are now » (Macrobius Saturnalia 111.13.16).

33 Martial Epi 13.82 ; Ausonius Epist 21 ; Seneca 3.17.2 ; Petronius Satiricon 36.3 ; Pliny HN 9. 66 ; Martial 7.27.8 ; 11.27.

34 Horace Sat 2.8 ; 2.4.63-9 ; Willis 2005, p. 8.4.4 ; Biddulf 2008 p. 91-100.

35 Curtis 1991, p. 159-175 ; The difference in volume sold can not be calculated as capacity of amphorae are rarely recorded but it does seem as though by volume more liquamen was sold than garum.

36 Grant 2000, p. 138 ; 141 ; 146.

37 Galen Opera Omnia ed. C.G. Kuhn (1965 reprint of 1823 edition Hildesheim George Olms) Bk 12.637. (comp. med.sec.loc) « For the stench of wounds that (remedy) which is called “of the Spanish”. Take : black garos, called oxyporum by the Romans, 1 sextarius, squill vinegar, 1 sextarius, Attic honey, 1½ ; boil until it binds, and put it away in a glass vessel and use ». Translation with gratitude : Justin Mansfield.

38 A Latin translation of this remedy made in the Renaissance, gives the following translation of the 2nd line »gari nigri quod Romani sociorum appellant.« (black garum which the Romans call « of our allies »). Galeno 1537, p. 361.

39 Apicius 1.32 ; Columella 12.59.4. Garum in a remedy : Columella 6.9.1 to treat fever in ox ; 6.34.2 to treat horses ; 7.10.3 to treat scrofulous pigs. Liquamen is used in veterinary remedies c.f. note 17.

2.5. Fish sauce in Galen

Galen’s use of fish sauce in his treaties on food and diet is valuable as there are numerous references to what we now know is a simple whole-fish garos which is blended with wine/vinegar and oil as a simple dressing for vegetables as we have come to expect. Lettuce for instance is boiled in the winter and served with olive oil, garos and vinegar while mallow and cabbage are served with olive oil and garos in order to ease their passage through the body. Galen also lists many pot herbs such as celery, hyacinth and rocket which are all served in a similar way 36. There is just one reference to black garos in Galen and it requires more consideration. The text is not that on food and diet which makes no reference to the black sauce at all which also supports the view that it was not used in the preparation of food, but one called « Medical compounds according to places » 37. The remedy is apparently called an oxyporium and considered a Spanish digestive and later versions of the text reference the idea that black garum was also called sociorum after the Spanish traders 38. Other medicinal recipes for oxyporium also make use of garum. In Apicius this remedy is mixed with vinegar and garum and this is in fact the only other direct reference to garum in Apicius that is not combined in a compound term and subsequently listed as a liquamen. This source indicates that black garum had a continuing medicinal role throughout the period even if it appears to be used less at table 39.

We cannot know when the blood viscera sauce was introduced into ancient cuisine. It certainly does not seem to be part of the early Greek evidence and its introduction may have been instigated by influence from Rome as the knowledge of these sauces spread. As a theory I offer the following : as fish sauces became generally more popular in Rome the elite would have been concerned with differentiating their foods from everybody else’s.

If the consumption of liquamen fish sauces made from small fish was widespread then the elite would create a demand for a luxury version. The manufacturer may have instigated new developments in fish sauce types to meet this demand. One of these would have been the blood and viscera sauce, though how they thought of it is quite bizarre to comprehend. Its expense meant that it functioned as a table condiment and the gourmet could control the bottle and discuss its merits to demonstrate his culinary knowledge. Other developments at this time may have been the use of much larger fish, that did have a market value as salted fish, such as mackerel, tuna and larger clupeidae and sparidae. We may surmise that the fashion for Greek culinary culture at this time would mean that the original term was retained to designate the new luxury black table sauce forcing the merchants and traders to coin a new term ; liquamen to designate the original small whole-fish sauce 40. Liquamen remained in the kitchen and invisible to the diner who only saw and valued expensive sauces at table. In the later Roman period as black garum was not as visible either in commerce or at the table, it was naturally taken for granted among some commentators, as it has been today, that garum was just the Latin for garos and it began to be used to designate the single primary product. Only this seems to explain the group of late and early medieval references that claim that garum was equivalent to liquamen 41. They must have genuinely believed at the time that it was and simply did not comprehend the complexity behind these products.

2.6. Muria and the Ausonius letter 21

The letter sent by Ausonius to his friend Paulinus in the early 4th century is quite intriguing and deserves to be quoted in full.

« Fearing that the oil you sent me was not pleasing, you repeated your gift and distinguished yourself more fully by adding a condiment (of muria 42) from Barcelona. But you know that I have neither the custom nor the ability to say the word muria, which is in use of the common folk, although the most learned of our ancestors and those who shun Greek expressions do not have a Latin expressions for the appellation garum. But I, by what ever name that liquor of our allies is called, “now will soon fill my patinas so that that juice (sucus), more sparingly used on our ancestors tables, will flood the spoons” …. » 43

The issue of the difference between garum and liquamen can be dealt with quite easily : if he believes that there is no Latin expression that he can use to replace garum then liquamen clearly cannot be equivalent to it. That he associates it with sociorum suggest he has received a blood/viscera sauce and there is no term in Latin for this. What requires explanation is his apparent use of muria to designate the sauce he has received.

Muria is primarily a brine ; that is, salt and water. It is also defined as the brine that salted fish are stored in (muria salsamenti) 44. Muria appears very rarely in Apicius and seems not to have been a regular part of the cook’s seasonings in the preserved recipes. This product is seen as a lower status form of seasoning but we have seen that a form of fish-brine was used in elite 4th c. Greek cuisine as an ingredient in dipping sauces and this combination is also found in references to food in Roman satire, so muria could potentially be desirable and especially if aged 45. Muria may have been valued because it was a « clean » sauce i.e. free of fermenting viscera, which was perceived as putrefaction 46.

Martial’s epigram on muria that follows the one for garum sociorum has often been seen as evidence that muria could in fact designate another garum made from tuna blood and viscera 47.

« Amphora Muriae

I am the daughter, I admit it, of Antipolitan tunny. Had I been of mackerel, I should not have been sent to you ».

It is fair to say that it is not logical, to have another term to designate the blood/viscera sauce which can also mean a completely different less valued product entirely. However the perception of muria as low status is deceptive as we must ask for whom is it inferior and where it fits in the sliding scale of fish sauce quality. Martial has, I think, juxtaposed garum with muria here because they represented the two different types of sauce that could be valued in Roman cuisine rather than offering two that were virtually the same. After all what can be said of the differences between one lot of fish viscera and another !

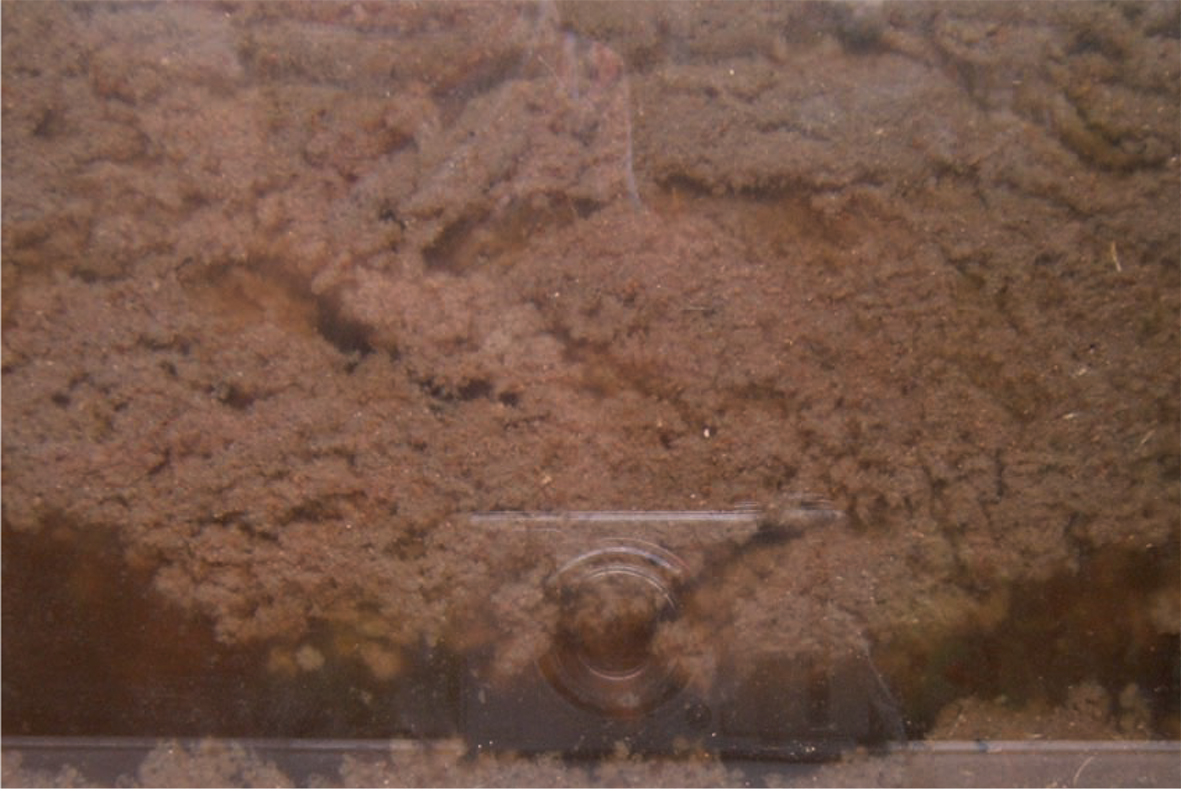

We do not know the volume of tuna caught in the Mediterranean but given the potential size of this fish it is likely to be large and the volume of muria generated clearly had a market. However I suspect that tuna was not used to make a liquamen but only made garum or muria as a secondary product to the salted fish 48. It is apparent that tuna muria could be aged and would mature in flavour and value 49. Tuna would also generate vast quantities of viscera and blood which would make tuna garum just as the Geoponica advocates and archaeological evidence confirms the use of tuna blood in the production of garum haimation 50. This poem and amphorae tituli picti suggest that mackerel actually served as the best fish to use both for muria and garum. The elite therefore would consider tuna muria a product for everyone else to consume. Everyone else actually represents the thriving middle in Roman society, not the poor. We may also propose that garum could be made from a mixture of many types of fish blood and viscera and this would ultimately represent the lowest quality garum. Horace has one gourmet tell his guests that their oenogarum was made with muria and another who makes it with garum 51. I had considered that this muria consuming gourmet was being ridiculed by the poet but clearly it is not that simple. The choice of which sauce to use in a given circumstance will depend on factors we do not necessarily understand. In the late empire liquamen is also described as a vulgar term in contrast to garum, but this does not mean that liquamen « per se » was necessarily lower class or cheaper ; this would depend on its origin, variety, manufacturer and recipe used 52. I have conducted many experiments to manufacture liquamen fish sauce and though they cannot be dealt with here in any detail it has been possible to demonstrate that long term storage of the unfiltered sauce results in exceptional nutrition 53. An image of an unfiltered mackerel liquamen sauce can be seen in fig. 2 where the residue or allec is floating on the top of the clear enriched sauce. When this bone-free residue was re-brined and left for a few months, a relatively good quality second sauce was generated and which we find described on the price edict 54.

Returning to Ausonius’ letter, these discussions have allowed us to see that he strikes a lofty pose and looks down on muria which he suggest is a vulgar term and we therefore assume it is a cheap and commonplace ingredient but vulgar is clearly a relative cultural idiom and from his lofty position is clearly the term that everybody else uses. He appears to be discussing the very idea of fish sauce seasonings generally and, as he does not want to use garum and as he has not received liquamen, he is using the only other term at his disposal : muria, which is only slightly lower quality than the garum sociorum that he values. At the same time he acknowledges that it is inadequate and expresses some frustration over the issue of what to call whatever he has received : « by what ever name that liquor of our allies is called. » That he has received a black garum is fairly clear but this letter also demonstrates that in the late empire fish sauce terminology had become a complicated issue.

40 The term liquamen is cognate with liquere/liquescere meaning « to be liquid » and « liquefy ». Isidore of Seville in the 6th c. defines liquamen as « little fish dissolved during salting produce the liquid of that name » and defines garum as the « juice of fish » Etymologiae 20.3.20. Corcoran 1962, p. 205 was the first to be confused by the Isidore definition and combine the liquor from salted fish (muria) with the sauce derived from dissolved fish.

41 Caelius Aurelianus 5th c. medical writer Chron 2.3.70 « ex garo quod vulgo liquamen appellant » ; 2.1.40 « vel garum quod appellamus liquamen » See partic.Beda Gramm. 7.279,10 « muria id est garos » which in the 7th c. may refer to the fact that in Roman Palastine muria/ies seems to have been the term for the primary product i.e. liquamen (Weingarten 2005).

42 This first muria is out of place and is not needed in the sentence. It seems strange that he used it at all having subsequently declared that he doesn’t like the term. Andrew Dalby (per. com.) has suggested that this first muria is a gloss and I am inclined to agree.

43 Ausonius Ep. 21 (Translation C Grocock) That he claims this sauce was « more sparingly used on our ancestors tables » is difficult to comprehend as noted by Corcoran (1963, p. 205).

44 Cato RR 7 ; Columella 12.55.4 ; Gargilius Martialis, Curae boum ex corpore. 4 ; Pliny, HN. 31.83-92 For its low status image c.f. Isidore of Seville Etym. 20.3.20.

45 Horace 2.4.63-9. An amphora tituli picti from London suggest that young tuna could be aged for 2 years. This cannot be whole fish as it would not be fit for consumption at that age and therefore muria is likely though un-named. Tituli picti also suggest muria could be aged Curtis 1991,p. 197. http://www.museumoflondon.org. uk/Collections-Research/Research/Your-Research/Londinium/Lite/ classifieds/sauce.htm (19/10/2012).

46 Seneca. Epist 95.25 « A costly extract of poisonous fish which burns up the stomach with its salted putrefaction ».

47 From the use of tuna viscera to make the haimation or bloody sauce in the Geoponica. Martial Epigrams 13.103 ; Corcoran 1963 p. 206 ; Studer 1994, p. 195.

48 Curtis 1991 p. 6. One may imagine the non-viscera waste matter from such a large fish generating a cheap muria too.

49 See above note 45. There is a modern fish sauce called colatura di Alici tradizionale made in Salerno Italy which involves very time consuming evisceration of tiny anchovy. The absence of viscera which provides digestive enzymes makes this sauce unusual. The sauce takes a year to completion and the tradition may go back ancient times and derive from a desire to make a « clean » fish sauce. It claims to be a garum, but has more in common with a muria. http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=GVGaz5yT67E.

50 Tiny gill bones from tuna have been found in a storage vessel in Aila Aqaba Jordon (Van Neer 2008).

3. Conclusion

It has been possible to see that each type of fish sauce could have had different roles within Roman cuisine. The sauce made just from blood and viscera is clearly sufficiently different in taste and flavour from the whole-fish sauces and fish brines to warrant the development of specific and sophisticated roles for all three sauces, which may have been instigated by apparently proactive Roman gourmets.

There is a complex social order behind the consumption of these multiple varieties and qualities of fish sauce which would benefit from further study. When talking of fish sauces in archaeology and history it is now necessary to be much more precise and stipulate if possible which kind of fish sauce is being referred too. One could buy aged elite black mackerel garum, ordinary black tuna garum, elite liquamen cooking sauces made from mackerel or cheaper cooking sauces made with a mixture of clupeidae and sparidae, or a tuna or mackerel muria, both of which could also be aged or new. All of these products could also come in second or even third grade versions. Distinguishing between them will not always be possible in the archaeological record but a recognition of the diversity is essential. It is also no longer adequate to simply refer to a single product called garum as the term cannot convey the complexity of these products and its use actually confuses more than it aids our understanding of the fish sauce trade. It is clear that the perception of the quality of these products depends on many factors : the particular taste of the consumer, the particular role the sauce will have in the meal and whether that meal is everyday or a rite of passage feast as well as the purchasing power of the consumer and where the consumer is placed and places himself in the social order.

51 Horace sat 2.4.63-9;2.8.

52 See note 8 above. Curtis 1991, p. 195 where he sites many tituli picti of named manufacturers.

53 Grainger forthcoming ; Grainger 2010.

54 see note 3 with ref to the bone free allec.